Gabriel Miller

Editorial Director

Medscape Oncology

Loading...

Gabriel Miller | September 28, 2016

Although the field of patient-centered medical technologies is relatively young, many technologies, especially those that tether to smartphones, are beginning to have an effect on the practice of medicine.

At the basic end of the spectrum, some health systems now allow patients to view all of their lab results, notes, and scans on a smartphone app from anywhere in the world; at the more complex, diagnostic end, smartphone apps are now capable of monitoring heart rhythms and measuring glucose or albumin concentrations. In terms of patient care, in some US cities, a smartphone app can now deliver a doctor to a patient's doorstep in as little as 20 minutes.

In August, Medscape surveyed 1423 healthcare providers, including 847 physicians, and 1103 patients to assess their attitudes toward these and other emerging technologies in medicine; the survey follows and expands upon a similar survey done in 2014 by Medscape. The results suggest that although patients and physicians agree that technology holds a great deal of promise for the delivery of medical care, there are important differences in what role exactly these technologies should play.

Smartphone apps to monitor blood glucose levels or cardiac irregularities have already arrived and are in use by patients.

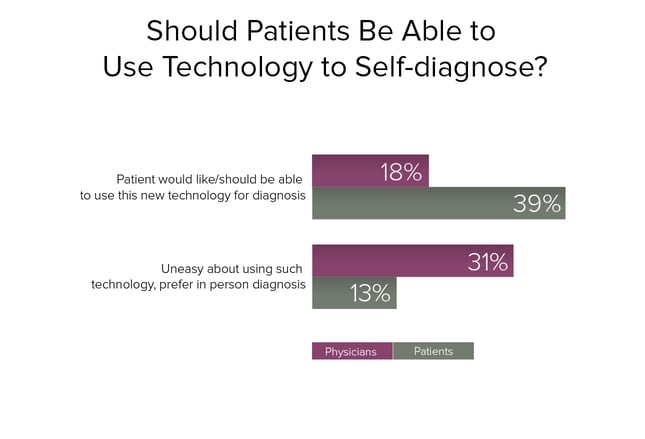

When patients and physicians were asked whether they support taking this technology one step further—using technologies to self-diagnose non–life-threatening medical conditions—twice as many patients as physicians said they did.

Conversely, twice as many physicians said they are uneasy about the introduction of these technologies.

Around one half of all respondents—whether patient or healthcare provider—said they were comfortable with a novel technology performing a test, but that all final diagnoses should be made by a qualified health professional.

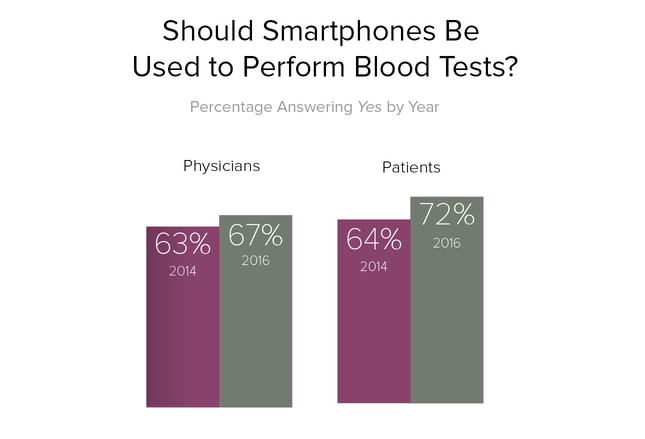

Patients and physicians were asked this same question by Medscape in 2014.[1] Since that time, both groups, but patients more so, have grown more comfortable with this approach to routine blood tests. Physicians in particular showed similar rates of approval for smartphone-based blood tests regardless of age, practice location (urban, suburban, or rural), or primary care vs specialist.

Although patients' and physicians' attitudes have not changed dramatically over the past 2 years, the technology has. Patients can now monitor routine lab values, such as cholesterol, fasting blood glucose, and triglyceride levels, using devices that tether to a smartphone. And, of interest in remote or economically disadvantaged locations, physicians can now use a smartphone-based device to run tests for sexually transmitted diseases, such as HIV and syphilis.

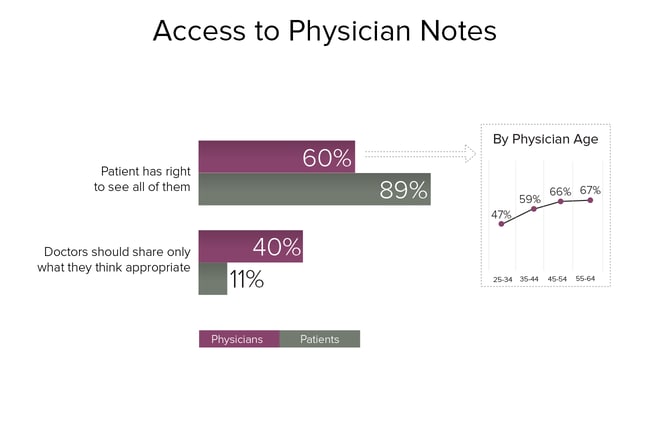

Not surprisingly, physicians and patients disagree widely on how much access patients should have to physician notes. Even so, 6 of 10 physicians felt that patients have the right to see all physician notes.

When analyzed by age, the survey results suggest that many physicians have become more comfortable with the idea of sharing their notes with patients as they have matured in clinical practice. Fewer than one half of physicians younger than 34 years said that patients should be able to access physician notes, whereas two thirds of physicians older than 45 years agreed that physicians should share their notes with patients.

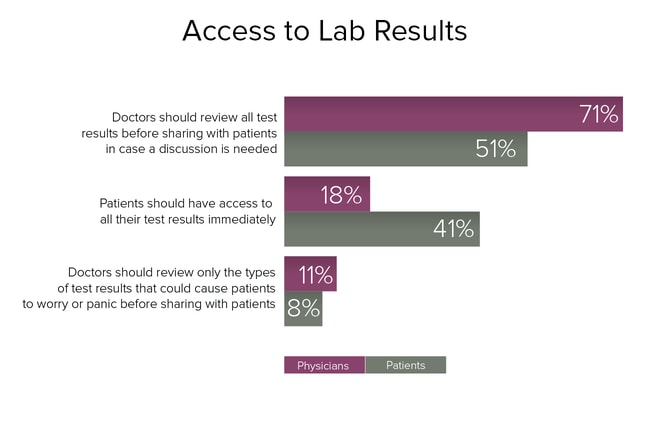

Twice as many patients as physicians felt they should have access to lab results as soon as they are available, regardless of whether they might cause patients to worry or panic.

Physicians wanted to have more control over how and when lab results were released. More than 7 of 10 physicians felt that they should review all lab results before providing patients with access to the results.

Patients with cancer in particular exemplify the risks of immediate access to lab results. In some cases, the release of test results depends on how a patient portal is configured, and in some instances patients may be able to see results of such tests as tumor markers—a potentially high-anxiety experience—before their physician has been able to put the results in context.

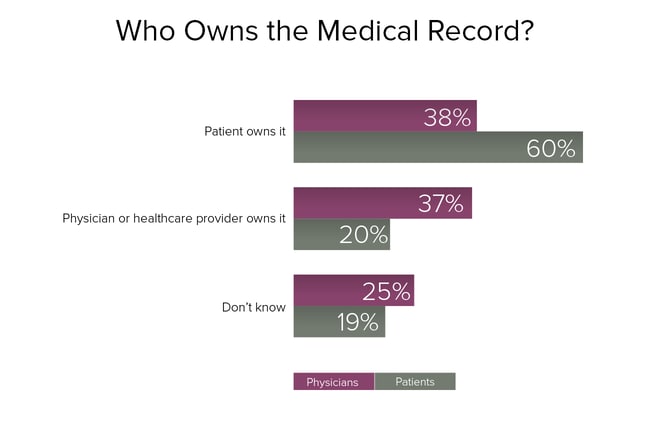

A significantly greater percentage of patients than physicians believe that they own the medical record. And overall, physicians were split, with an equal number granting ownership to themselves and their patients.

The results underscore that the question of medical record ownership is a confusing one for patients and physicians alike. A significant minority—25% of physicians and 19% of patients—said they didn't know.

In fact, medical record ownership is regulated on a state-by-state basis.[2] Many states have no laws governing ownership of medical records; a few, such as California and Texas, have laws supporting physician ownership, whereas one, New Hampshire, expressly grants ownership to the patient.

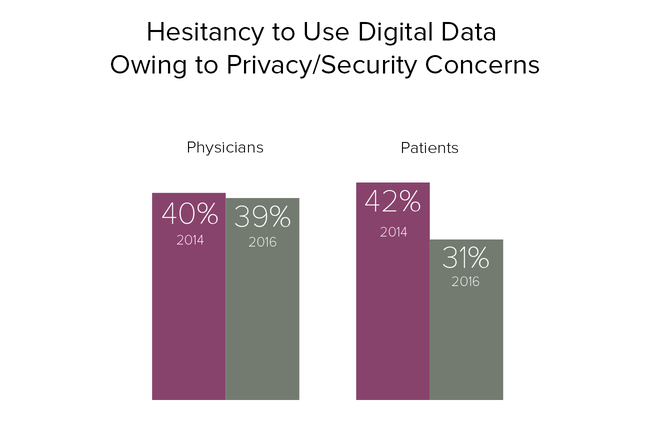

Since 2014, patients have become significantly more comfortable with the security of digital health technology and electronic health records (EHRs).

However, despite the near-universal adoption of EHRs in physician practices—in a recent Medscape survey,[3] 91% of physicians said they were currently using an EHR—physicians have not grown more comfortable with the security and privacy of digital health technology over the past 2 years.

By one measure, in fact, the security of digital health technology has decreased dramatically: the number of data breaches and cybersecurity attacks against healthcare organizations. Over this same 2-year period, the number of these attacks and data breaches has soared. According to a recent report by the Ponemon Institute,[4] since 2014, 89% of healthcare organizations have suffered at least one data breach, costing an average of $2.2 million per incident.

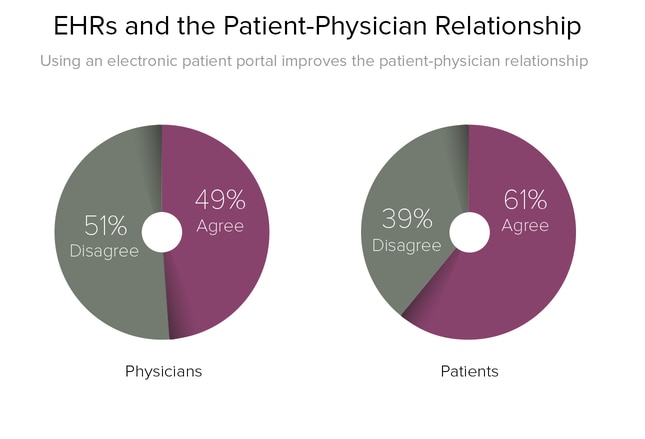

Patients were significantly more likely to agree that using an electronic patient portal to communicate with their physician was beneficial.

Despite patients' relatively greater support of such portals, there isn't consistent evidence that using a patient portal translates to better care or patient outcomes. A 2013 review[5] that included 14 randomized controlled trials found that "there was no consistent evidence that access to a patient portal significantly improved clinical outcome, satisfaction or adherence to treatment."

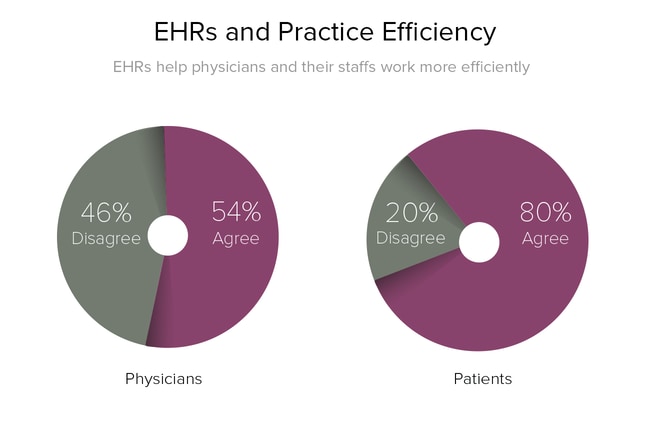

One of the most significant differences between patients and physicians was in their perception of how EHRs affect a practice. EHRs are often touted as a way to improve practice efficiency, and an overwhelming majority of patients—4 out of every 5—believe that EHRs help physicians and their staffs work more efficiently.

However, many physicians saw EHRs quite differently—about 1 out of every 2 physicians reported that EHRs either made no difference or reduced their efficiency. These results mirror those reported in a recently published, separate Medscape survey specifically on EHRs.[3] In that survey, a majority of doctors reported a reduced overall workflow with EHRs, and a majority also reported that EHRs decreased the amount of face-to-face time they had with patients.

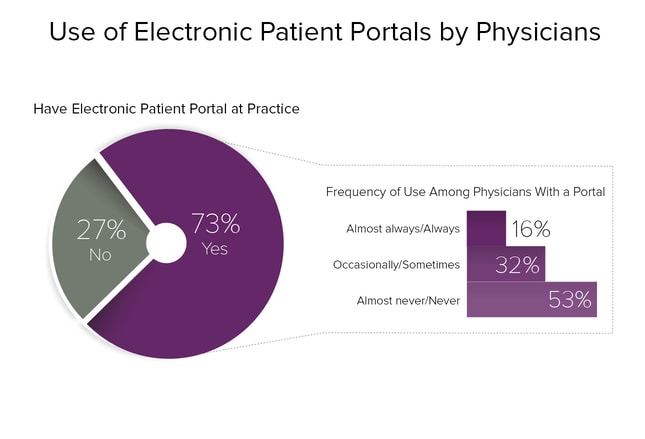

Patient portals have achieved a high degree of penetrance into clinical practice, with nearly three quarters of physicians reporting their integration at their main practice site.

However, despite this high penetrance, a majority of physicians—53%—reported that they rarely used this technology to communicate with patients.

Younger doctors and primary care physicians of all ages were more likely to have and use patient portals. For example, 82% of physicians 25-34 years of age reported having a patient portal, compared with 51% of physicians 65-74 years. And among primary care physicians, 80% reported having a patient portal, compared with 69% of specialists.

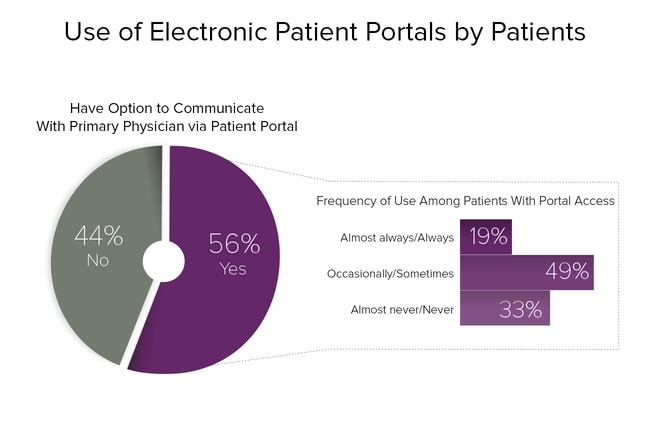

Patients reported lower availability of patient portals than physicians; however, they were significantly more likely to report using them. Just 13% of patients reported "never using" a patient portal; nearly one half reported using a patient portal at least occasionally, and nearly 20% reported using one "almost always" or "always."

The results suggest that patients prefer having another way to contact their physician and that a large majority of them use patient portals. Although there is no clear evidence that patient portals have a significant effect on patient outcomes, a 2012 review[6] of controlled trials found that patient portals decreased the number of office visits that patients made.

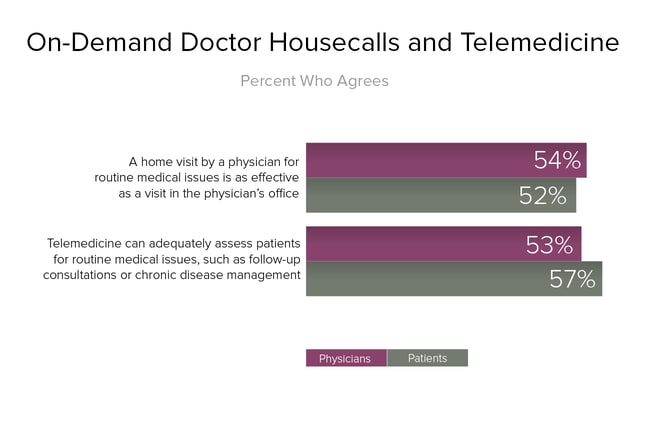

Patients and physicians showed similar levels of support for new approaches to delivering and receiving patient care, such as telemedicine and "doctor on demand" apps for smartphones and tablets.

Telemedicine apps, which offer on-demand video consultations with a physician or nurse, are growing rapidly. Some of the more popular apps include Doctor on Demand, which is backed by Google and the television personality Phil McGraw; Teladoc; MDLive; and American Well.

Many of these services tout themselves as solutions to the problem of access to primary care in the United States, where the average wait time to see a family physician is 19.5 days.[7] On this question, patients and physicians show a difference of opinion: 48% of patients felt that telemedicine tools can effectively help solve the shortage of primary care physicians in the United States, compared with just 35% of physicians.

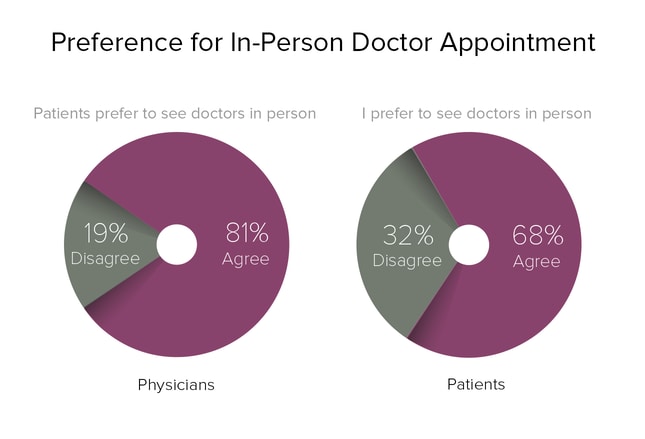

Physicians overestimated patients' preference for in-office visits. Whereas 68% of patients said they preferred to see a doctor in person, 81% of physicians said they believed patients preferred to see them in person.

Unlike questions related to patient portals or patients' access to physician notes, there was strong agreement by physicians of all ages as well as among specialists vs primary care physicians—a strong majority felt that patients preferred to see them in person.

Despite the difference, the overall results suggest that both patients and physicians continue to value an in-person appointment, even as telemedicine technologies gradually become more available.

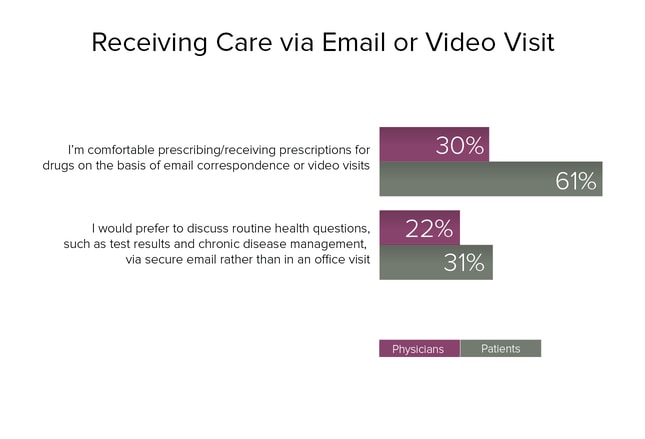

Patients indicated a much higher degree of comfort than physicians with managing chronic diseases and prescriptions via email or video visit. For example, more than twice as many patients as physicians said they were comfortable discussing and receiving prescriptions on the basis of email correspondence or a video visit.

Not surprisingly, a high proportion of physicians disagreed with the practice of writing prescriptions on the basis of email correspondence or video visits: 32% of physicians said they disagreed with the practice, and 13% said they strongly disagreed.

The 2008 federal Ryan Haight Online Pharmacy Consumer Protection Act provided a definition for the "practice of telemedicine" that allows prescribing even when there has been no physical encounter. However, states' laws exert a large amount of control over Internet prescribing, and regulations vary considerably from state to state. Generally speaking, a "patient/provider relationship" must be established before prescriptions can be written, with states variously determining whether this relationship can be established via online interactions alone.

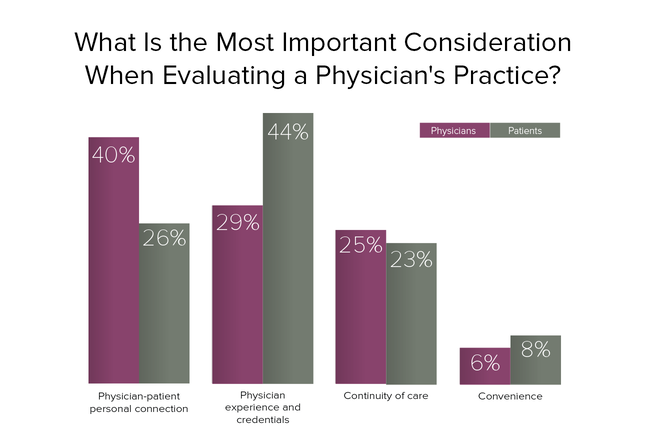

When asked to rank the most important aspect in evaluating a physician's practice, patients and physicians showed relatively sharp disagreement. Patients were significantly more concerned with a physician's experience and professional credentials, and much less concerned with the personal connection they felt to a physician. Alternatively, physicians felt that the personal connection they made with patients was the single most important aspect of the patient/physician experience, and that a physician's experience and credentials were less important.

Where did patients and physicians agree? That continuity of care is an important attribute—both ranked it similarly when evaluating a practice—and that convenience, which both groups ranked last, is not particularly important when choosing a practice.

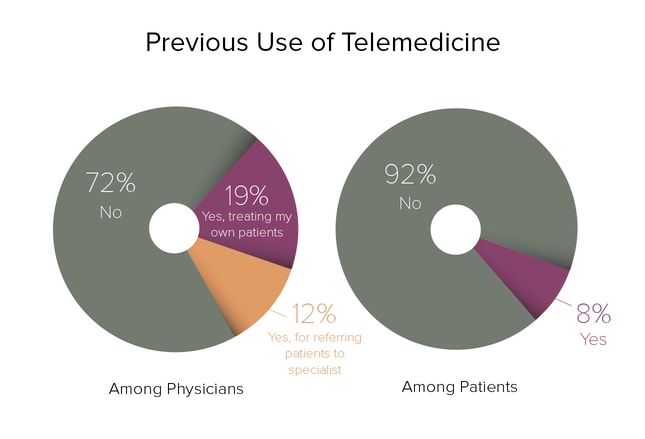

Despite patients' relatively stronger interest in telemedicine and new approaches to receiving care, such as "doctor on demand" smartphone apps, very few have used them to date.

However, nearly 1 in 5 physicians had used telemedicine, and 12% had referred a patient to a telemedicine visit with a specialist at some point. Referrals to a telemedicine visit were highest in rural areas, where 22% of physicians had previously referred a patient for a telemedicine visit.

Overall, physicians see promise in telemedicine for referring patients to specialists; of those who have yet to use it, 35% reported that they would be likely or extremely likely to make such a referral in the future. Rates were highest in rural areas, where 1 out of every 2 physicians said they were likely to make a telemedicine referral.

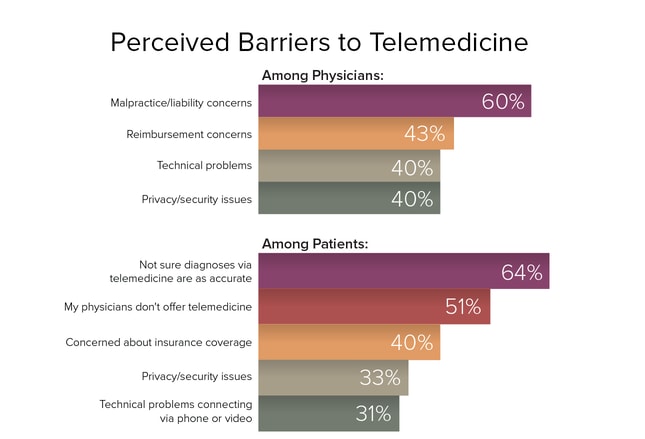

In terms of barriers to using telemedicine, patients and physicians expressed concerns that were unique to their perspective in the patient/physician interaction. Patients were most concerned about receiving an accurate diagnosis. The current lack of access to telemedicine was also perceived as a significant barrier.

Among physicians, practice issues were most important. Malpractice and liability concerns ranked highest among physicians. Reimbursement for physicians' time and effort ranked second, although technical problems and privacy/security issues were also seen as significant barriers for many physicians.

For physicians, perceived barriers to telemedicine varied depending on whether they practiced in an urban, suburban, or rural area. Physicians in urban and suburban practices were most concerned about malpractice liability, reflecting the overall trend; in contrast, physicians in rural practices felt that technical problems with telemedicine technology were a greater obstacle.

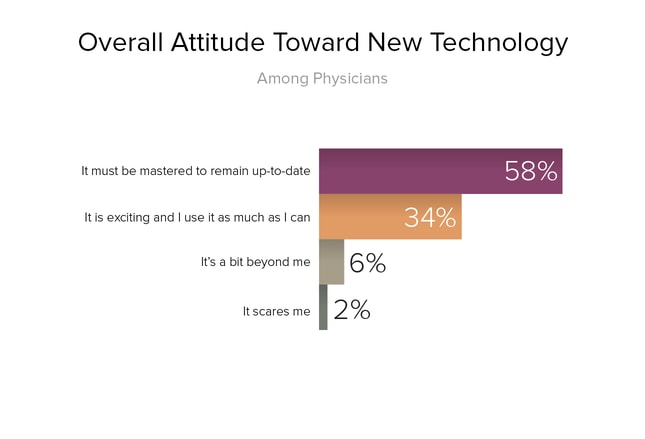

Whereas about one third of physicians reported that they are excited about new technologies in medicine, the majority of physicians—about 3 in 5—view incorporating new technologies into their practice as an obligation. In other words, they see it as a mandate by hospital administrators or a requirement to attest for meaningful use, or simply to stay current with practice standards.

Physicians' attitudes toward technology correlated with their age. The greatest proportion of physicians who felt that technology was exciting and use it as often as possible were younger than 35 years; in contrast, the greatest proportion of physicians who felt that technology was "a bit beyond me" were older than 55 years.

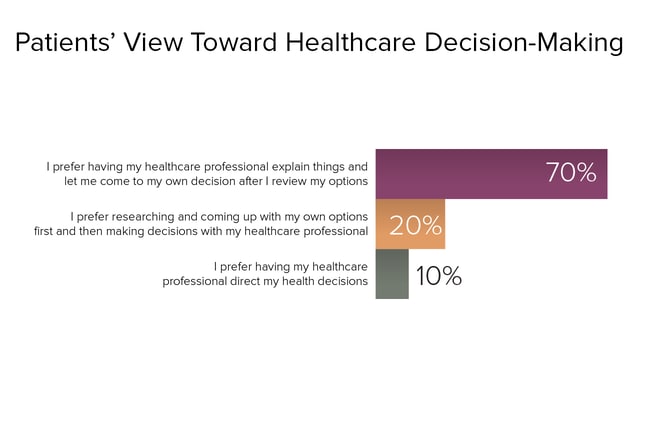

When asked to characterize how much input they prefer to have in the medical decision-making process, a vast majority of patients reported that they preferred their physicians to provide them with options and then come to a decision on their own.

However, a significant number of patients—1 in 5—preferred to take an even greater degree of ownership over their healthcare decisions, reporting that they preferred to do research and develop treatment options on their own in advance of an appointment before then making a decision in consultation with their physician.

Conversely, just 1 in 10 patients said they preferred to have their physician entirely direct their health decisions.

Previous

Next

Previous

Next

| 0 | of | 00 |