The treatment of resistant hypertension has received a boost with the recent US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of a completely new therapeutic approach that reduces activity in the sympathetic nervous system through renal denervation.

Two systems — Paradise (Recor Medical) and Symplicity Spyral (Medtronic) — gained approval last month after more than a decade in development. Following initial failure in early trials, the technology and techniques were refined, and the procedure has now been shown to lower blood pressure in many different scenarios.

The two devices have been given a similar, fairly broad indication: to reduce blood pressure as an adjunctive treatment in patients with hypertension in whom lifestyle modifications and antihypertensive medications do not adequately control blood pressure.

But how will these systems be used in clinical practice, and which patients will be prioritized for the procedure?

The Paradise system showed significant reductions in blood pressure in the three main sham-controlled trials: RADIANCE II, RADIANCE-HTN SOLO, and RADIANCE-HTN TRIO.

The Symplicity Spyral system was studied in two major trials. The HTN-OFF trial, in patients with hypertension whose medications could be discontinued, showed a significant reduction in blood pressure compared with sham-control patients. However, the SPYRAL HTN-ON study, in which patients continued taking their blood pressure medications, failed to confirm the significant reduction in 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring at 6 months seen in the pilot study. This apparently lower effect in the larger study has been widely attributed to higher medication use in the sham group.

The FDA's Circulatory System Device Panel reviewed the Paradise and Symplicity systems in terms of safety, efficacy, and whether benefit outweighs risk during back-to-back meetings earlier this year, and they were approved by the FDA on November 8 and November 20, respectively.

Most experts agree the two systems probably produce comparable reductions in blood pressure.

Ajay Kirtane, MD, director of the Interventional Cardiovascular Care program at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York City, who has been involved in several of the Paradise studies, says: "We are seeing a drop in systolic blood pressure with these systems of around 5 to 10 mm Hg from baseline, which is typically discerned at about 1 to 2 months after the procedure. I would say that after accounting for differences in medication utilization within the trials, the blood pressure reductions on the whole appear to be generally similar with the two devices."

The data show renal denervation is synergistic with other medications and that it can bring about an effect similar to a good antihypertensive medication taken as prescribed, Kirtane notes. So far, with follow-up out to about 3 to 5 years, the blood pressure reduction appears durable. "It's not something that I would anticipate having to do a repeat procedure in the same patient. The idea is to have it once and to get a durable benefit," he adds.

David Kandzari, MD, chief of the Piedmont Heart Institute, Atlanta, Georgia, who led the SPYRAL trials, says: "There is a lot of confounding that can occur in these trials, but if you look at the absolute reductions in blood pressure throughout the two programs, they are similar with the two devices."

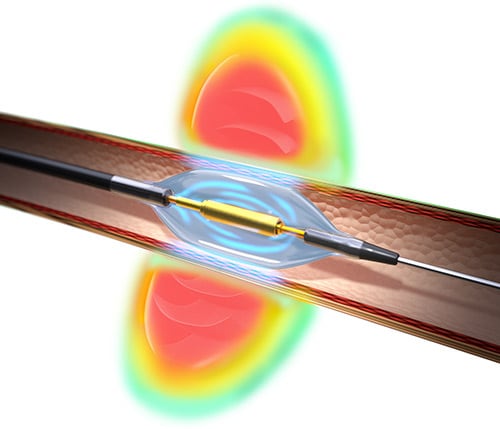

The two systems use different methods of ablating the renal nerves, with the Spyral system using radiofrequency energy while the Paradise system has adopted ultrasound technology. Both systems are incorporated into catheters that are directed to the renal artery during a short outpatient endovascular procedure in the cath lab.

Naomi Fisher, MD, director of hypertension at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, who has been involved in clinical trials for both companies, explained more about the differences between the systems.

The Symplicity Spyral system uses a catheter that has an electrode pattern in a helical arrangement, which allows ablation in all four quadrants either simultaneously or individually. Radiofrequency energy is delivered separately to the main renal artery, accessory arteries, and branch vessels to maximize the achieved denervation. Each ablation lasts about 45 to 60 seconds, and the average total ablation time in the clinical trials was about 15 minutes.

With the Paradise system, the transducer sits inside a balloon and delivers a circumferential ring of energy. The transducer is surrounded by a water-cooling system that circulates through the balloon to protect the arterial wall. The ultrasound energy is delivered in 7-second bursts to each main renal artery only, typically with two or three treatments to each artery, for an average total ablation time of about 40 seconds. Fisher points out that the procedure time may therefore be slightly longer with the Spyral system.

Kirtane notes that the renal denervation procedure does not work for everyone.

"In the studies, around two thirds of patients responded to the treatment. So, we have to be a little circumspect when talking to patients, as we don't know that they will definitely respond," he says. "We haven't been able to identify subgroups who respond better than others, but we are hopeful to be able to do this better in the future."

He also points out that at present endovascular access for the procedure is via the femoral artery, but future devices are expected to allow a radial approach, which should give easier access to the renal arteries, reduce bleeding, and allow patients to be more mobile more quickly.

Who Will Be Treated?

So, who are the ideal candidates for this new treatment? Everyone agrees that the renal denervation procedure should not be used in new patients with hypertension who have not engaged in significant lifestyle modification and use of antihypertensive medications.

"Certainly, lifestyle modification and medications should be first-line," Kirtane says. "That makes complete sense and will work for many patients. However, there are patients for whom these things don't always work, and they remain uncontrolled and at risk for cardiovascular events. And it is these patients who may benefit from the renal denervation procedure."

He described one of the first patients he treated with the Paradise device. The patient had already had a prior stroke and multiple hospitalizations despite being fairly young, and even with extensive lifestyle work-up and taking multiple antihypertensive medications, his blood pressure remained elevated. "We had tried everything, but he was still at high risk of another event. That is the type of patient — someone with truly resistant hypertension — who is likely to get this procedure in the first wave. There are many patients that fit this profile."

Then there are the patients who are taking two or three medications but are still uncontrolled. "So rather than escalating to a fourth or fifth antihypertensive medication, this may be an alternative option," Kirtane notes.

But there is also the very large pool of patients who are unwilling to take multiple antihypertensive medications.

Kirtane points out that despite the widespread availability of lifestyle modifications and medications, more than half of patients with hypertension do not manage to get their blood pressure controlled, and for many, it is because they have difficulty taking their medications. "There are a lot of patients like this who could be eligible; they too could fall under the approval indication, which is quite broad," he says.

"If a patient is completely unwilling to take medication because they have tried unsuccessfully in the past, and their systolic blood pressure is 170 or 180 mm Hg, as a physician if I have a therapy that could work for that patient I would certainly consider it and discuss it as a potential option for them."

Fisher has similar views. "The most obvious patients for whom this procedure should be considered are those who have resistant hypertension. These are patients who have uncontrolled blood pressure despite taking three or more medications from different antihypertensive classes at maximally tolerated doses."

But she points out that the pool of patients with this strict definition of resistant hypertension is smaller (at around 5% to 10%) than previously thought because many turn out not to be taking the three different medications, even if they have been prescribed.

"We've learned that many hypertension patients don't/can't/won't take their medications for a variety of reasons. Some have a long list of side effects when they take medications. Renal denervation could be very effective and helpful for those patients," says Fisher.

"But there are 110 to 120 million US patients with hypertension, and close to 75% are not reaching goal. There is a fear that floodgates are going to open," she added. "I think we will focus on the subgroup of these patients who are at higher cardiovascular risk and cannot get their blood pressure controlled for one reason or another."

Kandzari notes that renal denervation may be appropriate for patients who are already being prescribed medications but still have raised blood pressure, which he says represents about 75% of the US hypertensive population.

He also points out that patients need to have had secondary causes of hypertension excluded, have suitable renal artery anatomy, which can be ascertained with non-invasive ultrasound, and have reasonable renal function.

Reimbursement a Limiting Factor?

George Bakris, MD, director of the American Society of Hypertension Comprehensive Hypertension Center at the University of Chicago Medicine, Illinois, believes there will be a large demand for the procedure.

"There is no question that renal nerves are playing a role in resistant hypertension, and partial denervation of the kidney — which is what these devices are doing — will help with that," Bakris told theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology. He was involved in the early studies of Medtronic's first renal denervation catheter but is no longer affiliated with either company.

He says trying to decide who will get the procedure is a "conundrum" and will likely come down to cost.

"This is not just going to be a medical decision. It is going to be a business decision and will depend a lot on what Medicare/Medicaid and the major insurers are willing to pay," he explains.

Noting that the cost of the renal denervation procedure has not yet been established in the United States, but is likely to be at least several thousand dollars, much more than available antihypertensive medications, Bakris suggests that insurers are unlikely to allow widespread funding.

"My opinion is that if someone comes in with blood pressure of 150 mm Hg and says they don't want to take medications but would like the procedure, the answer will be no from the insurance companies. They will say take this $10-a-month drug instead. On the other hand, if a patient is already on three drugs with a blood pressure of 150 mm Hg and really doesn't want to take any more, then maybe they will be funded."

"I think to start with it will have a niche in the treatment of hypertension in patients who have tried the recommended traditional guideline approach and have adhered to this and are still uncontrolled," he says.

Bakris estimates that about 10% of US patients with hypertension have truly resistant hypertension. "If 10% to 20% of [these patients] wanted this procedure I don't think that would be unreasonable."

He says he can also see a place for the procedure in the millions of patients who just don't take their drugs. "While we may want to offer these patients this procedure, I can't see it being reimbursed for this group, at least to start with. I think it will be more like — if you want to do this instead of taking drugs that is your prerogative. But you're going to have to pay for it."

Kirtane agrees that reimbursement is likely going to be an issue.

"I think this may be a potential impediment in the beginning. We are waiting for the payors to come up with what they think is appropriate and how they think these devices should be used and reimbursed. There will probably be some criteria that make sense for them, such as a certain trial period of medication use. That would be very reasonable to expect. This will become much clearer in the next few months."

Both devices have been designated as breakthrough technologies in the United States, which allowed for accelerated approval, with the condition that there are rigorous post-marketing studies. Patients can therefore currently access the procedure by enrolling in these post-marketing registry studies.

Patient Demand

There certainly appears to be interest in the procedure from patients. "Surprisingly for many of us, patients really are quite keen for this," Fisher notes. "In patient preference studies, about one third of people said they would prefer a procedure to taking more medications to control their blood pressure. This is particularly noticeable among those who have experienced adverse effects on antihypertensive medications."

Kandzari agrees. "Patients are interested in renal denervation regardless of their blood pressure or how many meds they are taking, whereas physicians tend to think about it only for those with very severe hypertension or for those taking four or five drugs," he says. "All of the contemporary trials have been conducted in a broad population of patients with moderate hypertension, and I think it will be a broad spectrum of patients who will get this procedure."

Bakris points out that many patients with hypertension do not want to take medications at all. "They would rather go to the health food store and spend hundreds of dollars on something that doesn't work. Some of these patients may like the idea of a procedure if it means they don't have to take medication, but this group will find it difficult to get it funded."

Access to the procedure will also be dependent on training new operators, including interventional cardiologists, interventional radiologists, and vascular surgeons. It is currently available only at the major centers that have participated in the clinical trials.

Fisher said a training program is planned so that new centers can come on board. "We want to be able to expand the reach in a purposeful way to reflect the diversity of the population and to make sure this procedure reaches patients in more vulnerable areas."

A More Cautious View

Sandra Taler, MD, a hypertension specialist and nephrologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, who has not been involved in any of the renal denervation studies, says she is still cautious about the procedure.

One of the challenges has been showing these systems are effective. "The early studies were disappointing, and I was skeptical that this would come to anything, but the researchers were persistent," Taler said. "I presume they thought there was something there, and if they got the technique right, they could show a benefit. I think there will definitely be a market and there will certainly be patients that are asking for this treatment option."

But Taler says she's uncertain whether the benefit seen with renal denervation is convincing enough to justify a new and invasive procedure.

"Would I undergo this procedure where they put a catheter in to block the nerves around the kidneys? I'm not sure," she said. "You would want to make sure the operator has been trained properly. Every place is going to be quite new at it. While the centers that were involved in the studies would be a good place to go, I would be cautious about the new place on the corner."

Taler also notes the results appear varied. "They may be get a 5-10 mm Hg reduction. I would have to discuss with the patient how much this might benefit them. How much is it going to change their life and reduce their medication burden? People want to be cured and not to have to take any antihypertensive meds anymore, but I don't know how likely that is. I would think the chance that they will get off all drugs is relatively small. If they have to take two meds instead of three or four, or four meds instead of five, is that going to be enough of an incentive to go through this procedure?"

And although the safety results look reassuring so far, Taler points out that there will still be some risk attached. "Putting a catheter into an artery and advancing to where the kidneys are is not a risk-free procedure," she says. It could cause bleeding, potentially disseminate atherosclerotic plaque, and uses contrast, which also comes with risk.

"Older patients and those with more complex disease will be at higher risk of complications," she points out. "I'm sure some of these high-risk patients would have been excluded from the studies."

Taler also raises questions about long-term safety. "Those nerves innervating the kidney are there for a reason. How much do we really know about a denervated kidney? I just don't know whether there will be some negative repercussions from ablating the renal nerves."

Commenting on the safety of the procedure, Fisher says data so far have been "really excellent" for these devices.

"The main safety concern has been that the lining of the vessel wall may be damaged, but it turns out this appears to be very rare," she says. Out to 3 years in controlled trials, and longer in observed cohorts, there have been no major procedure-related safety events. The incidence of renal artery stenosis was extremely low, and there has been no evidence of kidney damage. "So, we are cautiously quite optimistic on safety."

Taler says she will go back and study the data carefully before discussing the procedure with her patients.

"I’m not completely against it, but I won't recommend it right away," she says. She sees it as an option for patients taking multiple medications who are still not controlled or those who can't tolerate medications. "There is a group of problematic patients like this, and they will probably be the first adopters."

Approved in Europe

In Europe, renal denervation systems have had CE approval for some time, but until recently, have not been recommended for use except in clinical trials.

However, earlier this year, after the publication of recent trials, the new European Society of Hypertension guidelines updated their position on renal denervation, assigning the procedure a Class II recommendation for use in patients with resistant hypertension. The guidelines also say the procedure can also be considered as an option in patients with uncontrolled hypertension despite the use of antihypertensive drug combination therapy or if drug treatment elicits serious side effects and poor quality of life.

Reimbursement, however, is different in different countries. As in the United States, some patients are receiving the procedure in post-marketing studies.

One hypertension expert who is skeptical about renal denervation is Franz Messerli, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Berne, Switzerland, and Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City.

He tells theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology that the technology is fully approved and reimbursed in Switzerland, but few procedures are actually being done; only 10 renal denervations were conducted at Swiss university hospitals in 2023.

"Interventionalists are of course keen to do it because they get paid, but hypertension specialists are not referring many patients. There is a feeling that it isn't a cost-effective therapy," Messerli says.

"I have referred a couple of patients, but I have not been very impressed with the results. The blood pressure went down for a few months but then drifted back up again," he notes.

He also points out that there are concerns about some patients who don't respond and may have a paradoxical increase in blood pressure following renal denervation. "When you compare this to a good antihypertensive drug like amlodipine, which lowers blood pressure reliably and consistently, for me the drug will always win."

More Long-Term Data Needed

Finally, also commenting for theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology, is Clyde Yancy, MD, professor of medicine at Northwestern University, Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois, and a past president of the American Heart Association, who has not been involved in the development of the technology. He described renal denervation as "a very clever and very intriguing novel approach to treating hypertension that has been shown to reduce blood pressure by about 6-7 mm Hg.

"That is not inconsequential. From a public health standpoint, that's enough to bring about a reduction in heart disease, myocardial infarction, and stroke," he says.

But Yancy calls for more data about longer-term effects.

"We need to know whether repeat procedures will be required and if there are any low-frequency high-acuity consequences that we have not yet realized. We also need to understand quality of life for patients, and ultimately, does renal denervation bring about a reduction in the end organ complications as effectively as antihypertensive medications," he says. "If all of those postulates are satisfied, then we will have an important new tool."

He stresses that the new technology should not be viewed as a shortcut or panacea. "I hope the patients who receive this are those that have made a decent effort at lifestyle modification and medical therapy and still haven't met blood pressure goals. I suspect that there will be some patients who will get this procedure because they want to take fewer medications, but I hope no patients undertake this procedure in lieu of medical treatments that we know to be effective in lowering blood pressure and reducing cardiovascular events," he says.

Yancy and Bakris both point out that this is an exciting time for hypertension, with other innovations on the horizon in addition to renal denervation. These include new more effective medications for resistant hypertension, some of which do not need daily dosing.

In the meantime, many are welcoming renal denervation as another tool for managing hypertension.

"Of course, we need to continue the post-marketing studies to ensure longer-term efficacy and safety, but I think it's exciting to have an additional therapy which is medication-independent and adherence-independent," Kirtane concludes. "Adherence to medication is such a major barrier in treating hypertension, and especially for patients who remain at risk, this offers another option."

Kirtane has reported being a lead investigator for the ReCor Paradise trials. Fisher has reported being an investigator for the ReCor Paradise trials and a consultant for Medtronic. Kandzari has reported being a lead investigator for the Symplicity Spyral trials. Messerli has reported being an advisor for Medtronic. Bakris, Yancy, and Taler have reported no relevant disclosures in the renal denervation field.

Comments