"CV Sports Chat" is an interview series that includes expert discussions relative to sports and exercise cardiology and the health care management of athletes.*

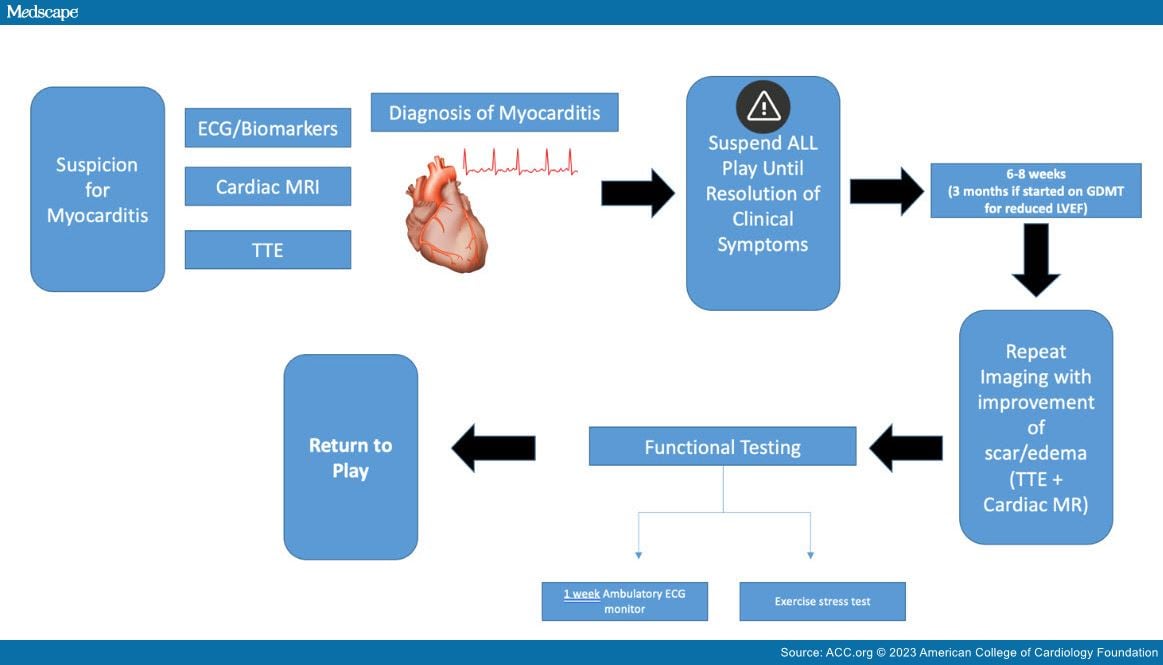

Myocarditis has received increased attention during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. However, it has long been recognized as a risk factor for sudden cardiac death in athletes with this diagnosis. The decision to allow an athlete to return to play can be nuanced and challenging (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Return to Play in Athletes With Acute Myocarditis. Courtesy of Hasnie UA, Martinez MW.

Dr. Matt Martinez is the director of Atlantic Health System Sports Cardiology at Morristown Medical Center and a nationally recognized expert in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The following is an interview with Dr. Martinez on his approach to "return to play in athletes with acute myocarditis."

How long is the time frame by which athletes can return to competitive action after their diagnosis of myocarditis?

Myocarditis is suspected in patients with cardiac signs and symptoms who present with a rise in cardiac biomarker levels, electrocardiographic (ECG) findings of acute myocardial injury, a new arrhythmia, or new ventricular systolic dysfunction.[1] It is a challenging clinical presentation to navigate because of marked heterogeneity.

As part of the return-to-play timeline, I generally use the resolution of symptoms as the starting point. That timeline is impacted by higher risk factors, including left ventricular (LV) and right ventricular (RV) dysfunction, persistently elevated troponin levels or ECG changes, symptoms with exercise, or persistent edema by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

In most cases, high-risk features are absent, so once symptoms resolve, I have athletes wait 6-8 weeks before we perform a repeat evaluation and before they exercise in any capacity. At that point, we repeat laboratory studies, ECG, and cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) to look for continued normal LV/RV function and resolution of edema, and to make sure there has not been progression of scar. Most often, scar is persistent at that time frame, but we do expect improvement in the edema by then.

After symptom and edema resolution, I perform a functional assessment with a symptom-limited treadmill exercise test to look for ventricular arrhythmias, effort intolerance, and reproduction of symptoms to guide their risk assessment. If all are normal, then we have the athlete wear an ambulatory monitor for a week as they start to return to exercise to ensure there are not any arrhythmias with return to usual exercise.

Which tests and imaging modalities are considered the most helpful for initial diagnosis, monitoring, and long-term prognostication?

Initial testing generally includes ECG, cardiac biomarkers, routine laboratory studies, and imaging. An echocardiogram is performed in all patients with suspected myocarditis to evaluate ventricular size and function, and to exclude valvular dysfunction or other potential causes of LV dysfunction. Coronary artery assessment is indicated in select patients with a presentation suggesting acute coronary syndrome and in those with high-risk features for ischemic heart disease. CMR in my practice is performed in essentially all athletes with suspected myocarditis to evaluate LV function and size while also looking for characteristic imaging features of myocarditis and concomitant pericarditis. These include inflammatory hyperemia and edema, as well as late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) suggestive of myocyte damage and scar.[2] A combination of clinical presentation and noninvasive features by CMR makes the diagnosis. CMR is the best tool we have for both diagnosis and for follow-up monitoring. There is prognostic value in the location of the CMR scar and the size of the scar burden; however, it is not unusual for the scar burden to be persistent by CMR, often up to 90% of the time. With scar, I initially keep a broad differential and consider alternative diagnoses such as sarcoid or arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy.

The use of cardiopulmonary exercise testing is variable for clinicians but can help assess athlete response to different levels of exercise. I typically will perform a symptom-limited exercise stress test to look for exercise-induced arrhythmias. I also use an ambulatory ECG monitor for a week while the athlete continues to exercise. Surveillance imaging is performed on a case-by-case basis.

When considering the return to play for athletes with a diagnosis of myocarditis, what is the overall strategy regarding reintroducing the athlete into the sport?

The focus is allowing the athlete adequate time to recover from the myocardial injury/inflammation. Improvement or resolution of symptoms is a good indicator that the myocardium is healing. Allowing the athlete to become symptom free by refraining from exercise with persistent absence of symptoms with usual activity are the next steps. Physical activity during the acute phase of myocarditis, especially in the setting of LV dysfunction or symptoms of heart failure, are thought to lead to adverse remodeling.

When an athlete has LV dysfunction, guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) helps foster normal cardiac remodeling the same as any other patient with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).[3] The goal is to reduce LV afterload, lower the heart rate for improved diastolic filling, and reduce preload as needed. I usually wait until 3 months of GDMT to repeat imaging, looking for improvement in LV function before considering any further exercise. Once LV function is restored and symptoms resolve, I begin to discuss exercise and determine an individualized plan for how to return to exercise and de-escalate GDMT.

Do specific sports have different considerations for return to play for athletes?

Even within an individual sport, the athlete's position makes a difference. Consider the exertional requirements of a kicker or a goalie compared with a wide receiver or striker. With every athlete, we tailor recovery to the needs of their sport as well as to the complexity of the myocarditis. Although there are not specific data, in my clinical practice, endurance athletes such as runners and cyclists generally have a longer duration before they return to play at their full level after myocarditis. That means that each athlete has a tailored discussion and plan for return to play, which usually entails a symptom-limited exercise assessment to prove they can tolerate the required exertional stress.

How do you handle persistent LGE/scar after myocarditis with respect to return to play?

Scar is persistent in most cases, but what is important is improvement/resolution of edema and normal ventricular function. In addition, aside from scar burden and edema is the distribution of the scar. For example, lateral wall epicardial scar is commonly seen with myocarditis and is generally considered to be lower risk. If the scar is present in the septal or midmyocardium, it is considered a malignant risk. When I encounter scar without active edema, I perform a symptom-limited exercise stress test to look for exercise-induced arrhythmias. If none are detected, I use an ambulatory ECG monitor for a week while the athlete continues to exercise. Assuming both are without arrhythmias, athletes continue to exercise unless limited by symptoms. Periodic cardiac imaging is done on a case-by-case basis.

What is the risk of recurrence in athletes, and which factors portend the greatest predictive value?

Fortunately, the vast majority resolve and myocarditis generally has a good prognosis. The risk of recurrence is related to high-risk features: ongoing symptoms, arrhythmias, persistent or worsening inflammation on CMR, or LV dysfunction.

*The interviews are edited for grammar and clarity.

Credit:

Brand X Pictures / Getty Images

© 2023 American College of Cardiology Foundation. All rights reserved.

Comments