At least a half-dozen times per year, an acute care physician sends me an ECG demonstrating a regular monomorphic wide complex tachycardia (WCT), asking me for my thoughts about the diagnosis. The backstory is almost always the same: The physician assumed that the WCT was a supraventricular tachycardia with aberrant conduction (SVT-AC) and treated it as such. The patient had a poor outcome because the diagnosis should have been ventricular tachycardia (VT). Consequently, the physician is criticized for poor decision-making and then sends me the case, hoping I will support their decision-making.

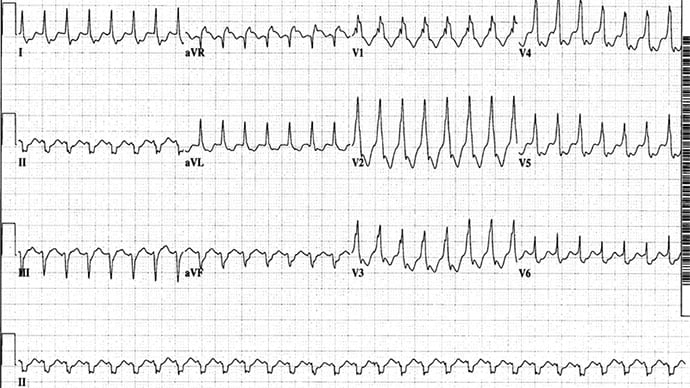

Figure. Courtesy of Amal Mattu, MD

The Figure demonstrates an example. This is the ECG of a 45-year-old man who presented to an emergency department in a country in which the specialty of emergency medicine was still developing. The patient was hemodynamically stable and had no history of coronary disease. The ECG was read as SVT with right bundle branch block. When two doses of IV adenosine failed to convert the patient's rhythm, two doses of IV metoprolol were administered. After the second dose, the patient suddenly became hypotensive (blood pressure 60/35 mm Hg). The physician attempted cardioversion, which led to ventricular fibrillation. The physician then defibrillated the patient, which resulted in return of spontaneous circulation. This near-death experience significantly compromised the level of respect for the emergency physician group within the hospital. The electrophysiology lab later confirmed VT.

These cases always perplex me. After all, one of the first "rules" that anyone training in emergency medicine learns is that you must always assume the worst-case scenario until proven otherwise. Chest pain represents acute myocardial infarction or aortic dissection until proven otherwise; abdominal pain represents a ruptured aortic aneurysm or mesenteric ischemia until proven otherwise; a headache represents subarachnoid hemorrhage until proven otherwise; and so on.

In regard to WCTs, VT is the worst-case scenario that must be assumed. It is important to note that no criteria reliably prove otherwise. The best study of various published algorithms for distinguishing VT from SVT-AC was by Jastrzebski and colleagues. They compared five highly touted electrocardiographic methods for differentiating WCTs and found that these algorithms missed 6%-40% of cases of VT. The bottom line is that although there are many reliable published criteria that help to rule in VT, there are no reliable criteria that rule out VT. Given the dangers associated with misdiagnosing VT as SVT-AC and the success of simply treating all of these patients as having VT, it makes the most sense to assume the worst-case scenario: Diagnose and treat all of these as VT.

The Basel Algorithm

Every couple of years we come across a new published algorithm or decision tools that attempt to once-and-for-all reliably distinguish between VT and SVT-AC. The most recent such attempt, the Basel algorithm (named for the city in Switzerland where the authors practice), has been receiving a great deal of attention on social media and in clinical discussions.

Moccetti and colleagues evaluated 206 monomorphic WCTs with electrophysiology-confirmed diagnoses and derived a three-question algorithm to distinguish between VT and SVT-AC. They then externally validated the algorithm using an additional 203 WCTs. The following three questions were used:

Does the patient have structural heart disease, defined by a history of myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure with ejection fraction < 30%, or an implanted device (eg, implanted cardioverter-defibrillator or cardiac resynchronization therapy)?

In lead II, is the time from the onset of the QRS complex to the first peak of the R wave or S wave > 40 ms?

In lead aVR, is the time from the onset of the QRS complex to the first peak of the R wave or S wave > 40 ms?

If none or one of the three criteria were fulfilled, then SVT-AC was diagnosed. If two to three of the criteria were fulfilled, then VT was diagnosed. They compared the Basel algorithm against two of the most well-known other systems, the Brugada and the Vereckei algorithms.

The authors found that the sensitivity, specificity, and overall accuracy of the algorithm for detecting VT was 92%, 89%, and 91% in the derivation cohort and 93%, 90%, and 93% in the validation cohort. These statistics were similar to those found for the Brugada and Vereckei algorithms, though the Basel algorithm was easier and faster to apply than the other two. However, when the researchers tested "real world" clinical applicability by evaluating the accuracy of eight other physicians (including two electrophysiologists, two general cardiologists, two cardiology fellows, and two internal medicine residents) using the Basel algorithm for WCTs, they found that the accuracy fell to 81%.

Viewpoint

If you are 80% accurate on your Board exam, you pass. But if you are 80%, or even 93%, accurate in diagnosing regular WCTs, you fail and patients may die. The good news is that if you simply assume and treat all of these as VT, the outcomes tend to be excellent. This is not groundbreaking news; we've all learned this before, and yet it is astonishing to me the number of times acute care physicians mistakenly diagnose and treat these as SVT-AC, with disastrous consequences. In fact, since this article was published, I've received three more such cases.

I know that some readers will be angry with me for "dumbing down" the recommendations, and they will insist that we should aspire to be smarter than using a one-size-fits-all treatment plan. But for many decades, brilliant cardiology researchers have been unable to find reliable methods to rule out VT and rule in SVT-AC when faced with a regular monomorphic WCT. The key message behind all of the studies is to tell us that there is no reliable way to rule out VT. Therefore, doesn't it make sense to just follow what the studies are telling us — treat all of these regular WCTs as VT — and end up saving every life? Definitive diagnoses can be made upstairs on the floors or in the electrophysiology lab with the benefit of more time and further testing. But in the busy emergency department, just call it VT, treat it as VT, and move on. Stop trying to outthink what the research has shown us.

Amal Mattu, MD, is a professor, vice chair of education, and co-director of the emergency cardiology fellowship in the Department of Emergency Medicine at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore.

Follow Dr Mattu on X (formerly known as Twitter).

Follow Medscape on Facebook, X (formerly known as Twitter), Instagram, and YouTube

Credits:

Images: Amal Mattu, MD

Medscape Emergency Medicine © 2023 WebMD, LLC

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Cite this: Wide Complex Tachycardia: SVT With Aberrant Conduction or VT? - Medscape - Oct 17, 2023.

Comments