This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome back to The Curbsiders. I'm Dr Matthew Watto, here with my great friend, Dr Paul Nelson Williams. We're going to be talking about some pearls that we learned about from a great guest that we talked to on our podcast, Dysphagia with Dr. Diana Snyder. Paul, first up is this: the difference between globus sensation and dysphagia. You had a clear picture of this, right?

Paul N. Williams, MD: I felt kind of okay before this, but I certainly felt much better afterwards. Why don't you talk us through it and define our terms?

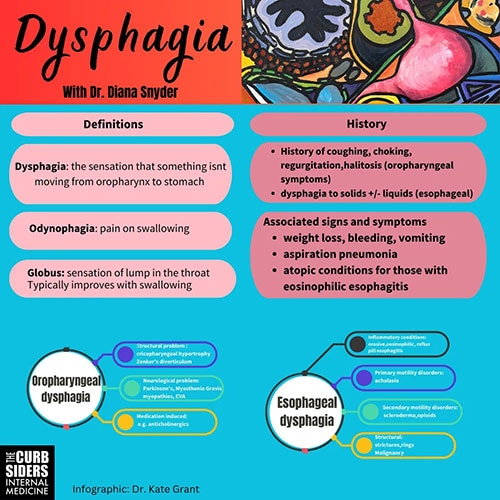

Watto: Dysphagia, of course, is difficulty swallowing, but globus sensation is where patients just have that sensation of something being stuck in their throat — a lump in the throat. This is such a simple distinction. If you ask the patient and it's primarily a problem at rest but it gets better with swallowing, it's probably globus sensation rather than dysphagia. Of course, "at rest" doesn't usually bother patients. It's really when they're swallowing. So, dysphagia is the opposite of globus sensation in many cases.

To view the original infographic, click here.

Now, Paul, when someone points to their suprasternal notch and says, "I feel like food gets stuck up here," can we put a lot of stock in that? What do you think?

Williams: Our speaker made the point that despite it being a long tube, the esophagus is actually a lot more complicated in terms of innervation than you might think. Patients are not great at localizing things. So, regardless of where they point to in their neck and say, "This is where food is getting stuck," that really doesn't give you much in the way of clues; you need to take a history and think about patient risk factors instead.

Watto: She gave us a list of things you can ask about to try to figure out if it's happening above the upper esophageal sphincter — more of an oropharyngeal cause.

If they start coughing and choking as soon as they initiate a swallow, that's a clue that it's coming from the upper esophageal sphincter. If they have nasal regurgitation of food, or if their friends and family are telling them they have really bad breath, that could be a clue. Sometimes people wake up and find food on their pillow that's not getting down their throat; it's sitting there and coming back up when they are sleeping. Those are some things you can ask about.

I was very surprised that she focused on one of the more common causes of esophageal dysphagia. And Paul, I was sad that it wasn't achalasia because I'm always tested on that. I was led to believe that it's very common. But please set us straight.

Williams: Unfortunately, manometry will not save you much of the time. We talked a lot about eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), which is not where I expected the episode to go, to be honest, because it's just not something I have thought about much.

It seemed more abstract and academic, but it turns out that it's not becoming more prevalent; we're just getting better at recognizing it. She made the point that if you have a younger patient who doesn't have a whole lot of risk factors who comes in with dysphagia, sometimes you have to tease things out. Because these patients have been dealing with it for so long, they compensate. They might be the person who sits at the table the longest, or they always have to take a drink of liquid after they eat something. They get used to making these adjustments. You have to take a bit of a nuanced history. But basically, in these younger patients with dysphagia, your differential is EoE for number one, two, and three, and then you can start worrying about other stuff. I don't think it quite occurred to me that achalasia is pretty uncommon, whereas she said the prevalence of EoE is 1 in 1000 or maybe 1 in 2000, but much more than you might expect.

Watto: Achalasia is like 1 in 100,000, so it's 100 times less common. Even among people getting manometry studies, true motility disorders are much less common than problems related to reflux or EoE or something else. But motility problems, even though we often think of them and test for them, don't happen as much. I seem to get a lot of the patients who say, "My esophagus was spasming." She said that most of the time, that's going to be from a more common cause, like reflux or EoE, so those patients will be worked up for those things.

Another pearl that we learned was another cause of a motility issue that I might never have considered: a medication we commonly prescribe. Were you aware of this, as someone who deals with a lot of patients taking chronic opioids?

Williams: The opioids thing surprised me. I'm used to the other end causing problems. I think we're all aware of opioid-related constipation, but as a cause of dysphagia, it was never on my radar. It wasn't something I thought to ask about. We talked about anticholinergics as a possible cause too, which makes sense.

Watto: We went way in depth on everything. She even told us how she runs a program at Mayo where patients learn how to self-dilate — basically like sword swallowing. Every morning they dilate their own esophagus so that instead of having to go in once a week for it to be done, they can maybe have it done once or twice a year. Fascinating stuff. She was a great guest. She gave really clear recommendations. I recommend that people click on this link to check out the full podcast with Dr Snyder.

Follow Medscape on Facebook, X (formerly known as Twitter), Instagram, and YouTube

Credits:

Image 1: The Curbsiders

© 2023 WebMD, LLC

Cite this: Matthew F. Watto, Paul N. Williams. Dysphagia: 'There's a Lump in My Throat' - Medscape - Oct 09, 2023.

Comments