Diabetes mellitus is a well-recognized risk factor for dementia. In prospective studies, diabetes confers a greater than 80% increase in risk for all-cause dementia and Alzheimer's disease, and greater than 180% increase in risk for vascular dementia.[1] One in seven adults in the United States are estimated to have diabetes, and more than 90% of them have type 2 diabetes (T2D).[2] With an aging population and increasing obesity, the incidence and prevalence of T2D is expected to continue to increase worldwide.[3]

Insulin resistance, which is a metabolic hallmark of T2D, has been postulated as a pathophysiologic connection between diabetes and dementia. Hyperinsulinemia, a biomarker of peripheral insulin resistance, is a risk factor for Alzheimer's disease even in the absence of diabetes.[4] At the same time, ex-vivo studies have shown evidence of brain insulin resistance in people with Alzheimer's disease who did not have diabetes.[5] While insulin signaling in the brain has an important role in neuronal and glial metabolism, synaptic neurotransmission, neuroinflammation and neurovascular coupling, it is presently unclear whether the observed associations between T2D and dementia are caused by insulin resistance in the brain or metabolic consequences of peripheral insulin resistance (as reviewed in Reference[6]). T2D is also characterized by endothelial dysfunction and microvascular insufficiency, which can lead to vascular dementia even in the absence of macrovascular insults, through mechanisms involving ischemia, blood–brain barrier leakage, and disruptions in white matter integrity.[7]

Given the strong epidemiologic and pathophysiologic connections between diabetes and dementia, it is not surprising that glucose-lowering drugs have been of interest for the prevention of dementia. In the current issue of the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, Tang and co-authors[8] aimed to resolve inconsistencies in the existing observational data by performing a systematic review and a meta-analysis to examine the associations between the use of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) and sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors in people with T2D and the risk for incident all-cause dementia, Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. Ten observational prospective studies that met the inclusion criteria for meta-analysis encompassed more than 800,000 people with T2D (44% men), with a mean baseline age of 68 years and a median duration of follow-up of 4.5 years. Included studies were predominantly deemed to be of high methodological quality, but with substantial heterogeneity. Seven studies involved DPP-4 inhibitor users who, compared to non-users, had significantly lower relative risk for all-cause dementia by 17% and vascular dementia by 41%, but without significant difference in the risk for Alzheimer's disease. Compared to non-users, users of GLP-1RAs (five studies) and SGLT2 inhibitors (three studies) had a significantly lower risk for all-cause dementia by 28% and 38%, respectively; meta-analysis by dementia subtype was not performed due to a limited number of studies.

It is important to consider the limitations of the findings of Tang and colleagues,[8] which stem from the limited number, heterogeneity, and observational nature of the studies that met the inclusion criteria in this meta-analysis. As the authors note,[8] the real-world treatment decisions in T2D are complex, and depend not only on the pharmacologic properties of different classes of glucose-lowering medications, but also on multiple other factors that could confound the observed associations. For instance, people who are older, have more comorbidities, and belong to ethnic and racial minority groups, have increased risk for dementia,[9] and at the same time are less likely to be prescribed GLP-1 RAs and SGLT2 inhibitors.[10,11] Another potential confounder is duration of diabetes, as people with T2D onset at a younger age have a higher risk for dementia,[1] and at the same time have a greater degree of insulin deficiency, and are therefore more likely to be treated with insulin than novel glucose lowering drugs. Included studies did not provide detailed information on concomitant medication use or medication usage in comparison groups. Among frequently used diabetes medications, some medications, such as metformin, could lower dementia risk;[12] other medications, such as sulfonylureas and insulin, can promote obesity and cause hypoglycemia, which can increase dementia risk.[13] These confounders could not be accounted for in Tang and colleagues' meta-analysis[8] due to the limited availability of this type of data in the published studies. Finally, the included studies were conducted primarily in European and Asian countries, and extrapolations to non-Caucasian and non-Asian populations, and non-single-payer health-care systems should be taken with caution.

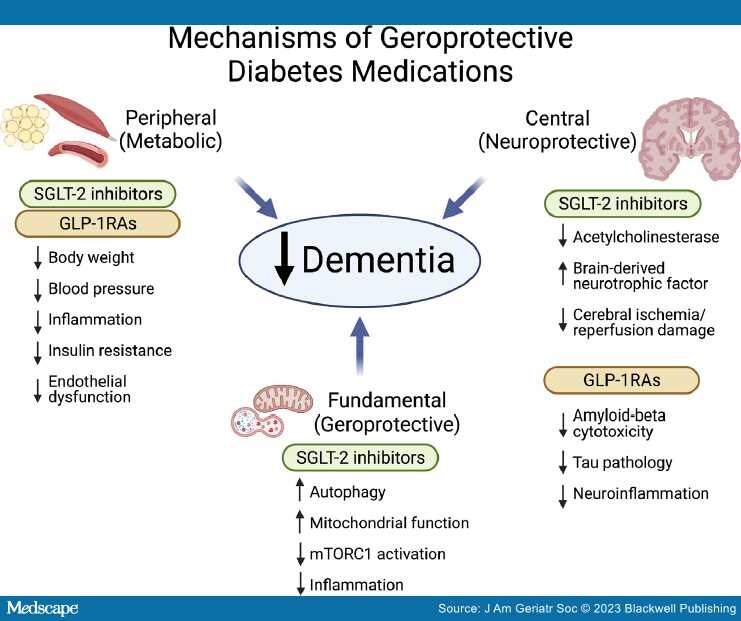

Despite the above limitations that are inherent to the meta-analysis of observational data, it is plausible that at least some of the observed associations are the result of biological effects of the newer glucose-lowering drugs. It should be noted that the beneficial effects of DPP4-inhibitors are attributed to an increase in endogenous GLP-1 availability; GLP-1RAs are more effective at the activation of GLP-1 receptors than the endogenous GLP-1. Therefore, it is not surprising that GLP-1RAs were associated with a greater risk reduction for all-cause dementia than DPP-4 inhibitors.[8] GLP-1RAs and SGLT2 inhibitors, originally developed to lower blood glucose, have been found to exhibit powerful pleiotropic effects which can roughly be grouped into three inter-related categories (Figure 1): peripheral (metabolic), central (neuroprotective), and fundamental (geroprotective). First, GLP-1RAs and SGLT2 inhibitors, beyond glucose lowering, ameliorate peripheral diabetes-related metabolic risk factors implicated in the pathogenesis of dementia, including obesity, hypertension, endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, and peripheral insulin resistance.[14,15] Second, the liposolubility of GLP-1RAs and SGLT-2 inhibitors and availability of GLP-1, SGLT-1, and SGLT-2 receptors in the central nervous system allow for direct central effects of these drugs.[14] Direct neuroprotective effects of SGLT-2 inhibitors may be mediated by inhibition of acetylcholinesterase, enhanced production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and protection from cerebral ischemia/reperfusion damage;[14] GLP-1RAs may reduce amyloid-beta induced neuronal cytotoxicity,[16] tau pathology,[17] and neuroinflammation.[18] Finally, SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1RAs may modulate fundamental processes involved in the biology of aging, which, according to the geroscience hypothesis, would reduce the risk for multiple aging-associated chronic diseases simultaneously. These "off-target" effects have been well documented for SGLT-2 inhibitors, which in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) improve cardiovascular, renal outcomes and all-cause mortality even in people without diabetes[19] and have been shown in preclinical studies to modulate aging biology processes by enhancing autophagy,[20] improving mitochondrial function,[21] and downregulating mTORC1 activation.[22]

Figure 1.

Postulated mechanisms by which newer diabetes medications with geroprotective properties may reduce incidence of dementia. SGLT-2—sodium-glucose co-transporter 2, GLP-1RAs—glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists, mTORC1—mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (Created with BioRender.com).

Despite the observed connections between diabetes and dementia, none of the available diabetes medications have been repurposed to prevent or treat cognitive decline in dementia. Should findings by Tang et al.[8] prompt the change in clinical practice toward tailoring individualized diabetes pharmacotherapy to reduce risk for dementia? Should we consider repurposing diabetes medications to prevent dementia even in people without diabetes? In the absence of RCTs adequately powered to assess cognitive outcomes, rigorously conducted observational studies and meta-analyses of observational data, such as the one by Tang et al.,[8] remain a valuable hypothesis-generating resource. Reassuringly, these findings suggest that patients with diabetes are not harmed by newer glucose lowering drugs, and may in fact benefit from health improvements not previously observed in RCTs. However, moving the pendulum toward repurposing diabetes drugs for indications other than diabetes will require well designed and adequately powered RCTs. In fact, the availability of high quality RCT data on cardiovascular, renal and mortality outcomes has led to regulatory approvals for the repurposing of SGLT2-inhibitors for the prevention of cardiovascular death, heart failure hospitalizations, and decline of kidney function in people without diabetes.[19]

After decades of research, we have yet to identify effective preventative and disease-modifying pharmacotherapies for either vascular dementia or Alzheimer's disease, beyond addressing the known risk factors. Compared to new drug discovery, repurposing drugs that are already in clinical use has benefits of known safety profiles, pharmacokinetics, and mechanisms of action (at least with regards to the "on-target" effects), which may translate into lower testing costs and faster regulatory approval for repurposed indications. Such efforts would still be a major feat, requiring large number of participants and years of follow up, as illustrated by the ongoing EVOKE and EVOKE plus phase III RCTs (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT04777396 and NCT04777409, respectively), which aim to investigate the efficacy of oral GLP-1RA semaglutide for prevention of cognitive and functional decline in people with early Alzheimer's disease. RCTs targeting primary prevention of dementia would require even more participants and study time, which would translate into even higher costs. One way to bypass the required long study duration needed to observe meaningful declines in cognitively intact older individuals would be to establish trackable biomarkers as reliable surrogate outcomes that precede development of cognitive and functional decline. Notable progress made in the research of blood-based biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease[23] provides hope that this goal is attainable.

In conclusion, repurposing drugs with pleiotropic metabolic and geroprotective properties for the prevention of dementia and other aging-associated chronic diseases is a promising avenue toward the extension of healthy longevity for an increasing number of people who live longer lives. GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT-2 inhibitors might herald a new era.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Sofiya Milman for review of the manuscript.

Sponsor's Role

None.

Financial Disclosure

Sandra Aleksic is supported by NIH/NCATS Einstein-Montefiore CTSA UL1TR002556 and KL2TR002558.

J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(7):2041-2045. © 2023 Blackwell Publishing