This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome back to The Curbsiders. I'm Dr Matthew Watto here with my great friend, Dr Paul Nelson Williams. Paul, we're going to be talking about insulin for diabetes, specifically type 2 diabetes. Dr Jeff Colburn had some good stuff to teach us.

Do you agree with me that when to start insulin on some patients is a bit of a gray area? There's room for interpretation sometimes.

Paul N. Williams, MD: I think you should feel that way. We should not be too algorithmic about when to start insulin because patients are individuals, and circumstances vary as to when you might start it. For me, double-digit A1c is probably a good place to start, and I think that's relatively concordant with the A1c guidelines. What else do you consider before you pull the trigger?

Watto: I asked you that question on the podcast, and you said, "When I've tried everything else." I usually think, What else is there? Both Jeff and Dr Marie McDonald (who also recently talked with us) said that if someone has catabolic symptoms — they are losing weight; they have all the polys (polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia) — that's a sign that they are probably insulin-deficient. They are probably going to need insulin at least temporarily, and you should think about it. So if I see catabolic symptoms, that's one time where I push a lot harder to get the patient on insulin because I'm worried that they have a severe deficiency, and we need to bring the glucose levels down and see where the dust settles. That's my practice now after talking with them.

Williams: These patients are glucotoxic, and you're not going to wring any more insulin out of the pancreas right now. They just need a little bit of exogenous help before it wakes up and starts doing the job if there's a job left to do. Once you've hit that point, they just need more help than we can give them with other non-insulin medications.

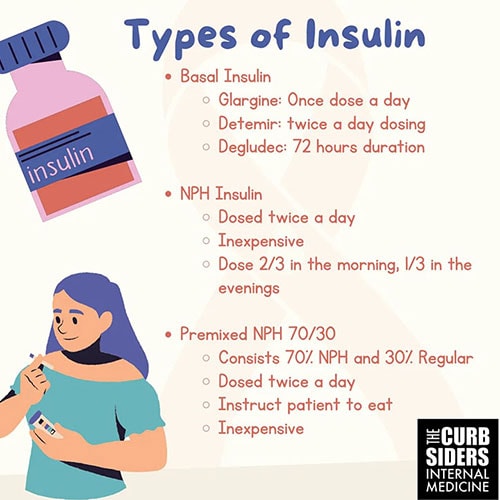

Watto: Now, speaking of insulin, most people are comfortable with using glargine or standard basal once-a-day insulin. I thought detemir was a standard once-a-day basal insulin because I commonly see it prescribed that way. But what did Jeff tell us about that?

Williams: This was practice-changing for me. Any time I looked it up, Dr Google says it's a one-to-one conversion between detemir and glargine. It's what I've seen in my geographic area; it seemed to be a once-daily medication. It turns out that the half-life of detemir is not 24 hours. You made the point that maybe people have been trying to cover the big meals by giving it just once a day. But it's really supposed to be a twice-daily medication. So you would give it in even doses: If someone was getting 10 units daily of glargine or neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) insulin, then you would give them 5 units of detemir twice daily. This is different from what I had been doing and certainly will be a change as I move forward.

Watto: It makes the most difference at the low doses, which you can imagine, because it hits a lower peak and it's going to be on and off faster at a low dose. If you look at the package insert, it says that at really high doses, it doesn't matter whether you give it once or twice a day. But when you are starting insulin, you're probably going to be starting it at 10 or 20 units, and it should probably in split dosing. That was also practice-changing for me. I have a few patients who are still on detemir but not taking it twice a day. I'm going to have to switch them up, especially if they're not doing well with their glucose control.

How do you recommend dosing NPH insulin after our discussion with Dr Coburn?

Williams: It's a stealth med because it's usually very affordable for patients. We are always fighting with insurance formularies and switching between different types of insulin. NPH has always been pretty cheap. As opposed to detemir, where you are giving the same dose twice daily, with this one, you would take two thirds of your total dose in the morning and one third in the evening, the idea being that the two-thirds dose would cover breakfast and lunch and then the one-third dose would cover the evening meal.

Dr Coburn made the point that patients have to eat lunch with this; it's not a meal they can skip because of the higher morning dose. They run the risk for hypoglycemia with that one. Patients should be consistent with meals if they are taking this medication. After speaking with Dr Coburn, I feel a little bit more comfortable and confident prescribing it.

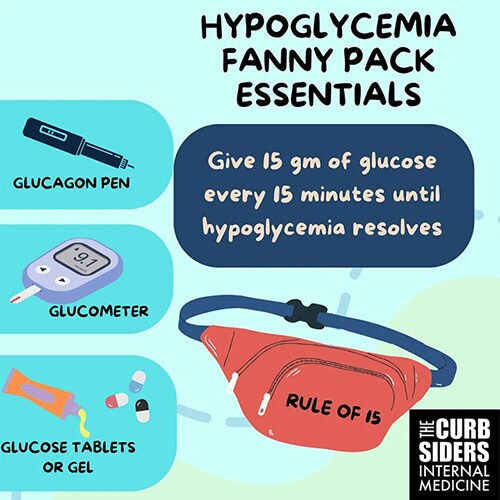

Watto: Jeff recommends carrying a fanny pack, not just because they're cool but also because it's a useful way to carry diabetes supplies. Did you find anything practice-changing about hypoglycemia?

Williams: Dr Coburn makes the point that any time you initiate insulin, you should be doing really straightforward and clear counseling about hypoglycemia and what to look for, how dangerous it can potentially be, and what your contingency plan should be. You mentioned the fanny pack. It's good form to have a glucometer with them at all times so that when they are having symptoms, they can check their blood sugar and counsel patients about what those symptoms would be, usually the adrenergic symptoms (feeling shaky, nervous, sweaty, and hungry). If they feel those things, they should check their blood sugar right away and then have a plan to treat hypoglycemia if it exists. We talked through a couple of options.

Watto: He said that even though candy tastes sweeter, it's made of sucrose which breaks down into glucose and fructose, so it's slower to get the glucose in. The glucose tablets or the glucose gel, which you can buy, have about 15 g of carbs. He talked about the rule of 15. Patients should take 15 g of carbs, wait 15 minutes, and check their glucose again. If it's not coming up, they should take another 15 g of carbs. If they need to repeat that more than three or four times, that's an hour that they have been hypoglycemic, and they should get to an emergency room because they might need a dextrose infusion.

Williams: EMS should be called at that point.

Watto: He also talked about glucagon, which is not something I've prescribed very often. Glucagon can only be given once in 24 hours because it depletes their glycogen stores and they would have to eat to rebuild their glycogen stores before glucagon could be effective again. The person should be in the recovery position because they often will vomit after they get glucagon.

It's important when treating people with insulin to know how to treat hypoglycemia. So get your patient a fanny pack and make sure they have some glucose tabs or gel and glucagon in there or whatever they are going to use for hypoglycemia.

To hear the full podcast with Dr Coburn, click here.

Follow Medscape on Facebook, X (formerly known as Twitter), Instagram, and YouTube

Credits:

Images: The Curbsiders

© 2023 WebMD, LLC

Cite this: A Fanny Pack Full of Tips for Starting Patients on Insulin - Medscape - Sep 12, 2023.

Comments