Graphical Abstract

Delayed AF ablation retains its efficacy.

When added to continued oral anticoagulation and good management of concomitant cardiovascular conditions, rhythm control therapy is slowly shifting from a symptom-directed treatment[1] to a pillar of outcome reduction in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) and stroke risk factors.[2] This change in clinical practice is based on the outcome-reducing effects of an early rhythm control therapy strategy observed in the EAST-AFNET 4 trial,[3] including in asymptomatic patients.[4] Early rhythm control therapy using a combination of antiarrhythmic drugs, supplemented by AF ablation in a quarter of patients at 2 years, is not only effective but is also cost-effective at accepted thresholds based on German healthcare utilization and cost data.[5] Analyses in electronic health records and population-based datasets demonstrate the safety of modern rhythm control therapy and replicate the outcome-reducing effect of early rhythm control in non-randomized analyses.[6–8] The resulting tectonic shift in the demand for rhythm control therapy is beginning to be felt across specialist AF services and is likely to intensify.

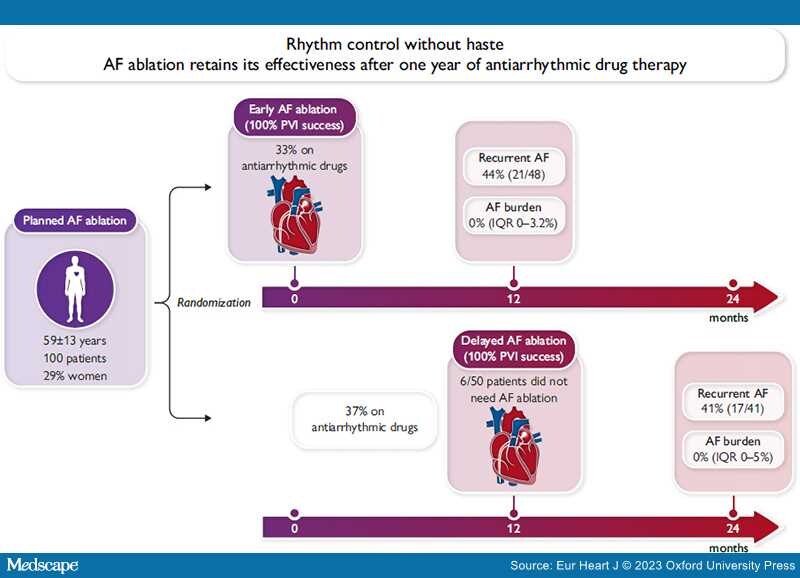

In this issue of the European Heart Journal, Jonathan Kalman and colleagues report the primary outcome of a small, well-conducted, randomized trial comparing the effectiveness of early AF ablation with that of AF ablation delayed by a year of antiarrhythmic drug therapy in patients with paroxysmal or persistent AF.[9] One hundred patients referred for AF ablation to two Australian centres were randomized to immediate AF ablation (within 30 days after randomization) or to a protocol-defined waiting time of 12 months on antiarrhythmic drug therapy followed by AF ablation. Accepting the delayed AF ablation strategy will have posed challenges for patients and care teams. The study found the important result that rhythm outcome 1 year after AF ablation is identical between immediate and delayed AF ablation. This was confirmed in the primary outcome of the trial, recurrent AF, in AF burden analyses, and in the need for antiarrhythmic drug therapy 12 months after AF ablation (Graphical Abstract). Interestingly, 6/50 patients in the delayed ablation arm did not undergo AF ablation after the 1 year waiting time, presumably because medical therapy was sufficient. Patients had a mean age of 59 years, were predominantly male, and had a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1.8 (early ablation) and 1.2 (delayed ablation). The findings are important for clinical practice, and we would like to congratulate the investigators for completing the trial. All patients in the trial received rhythm control aligned with early rhythm control in the EAST-AFNET 4 trial, where 75% of patients did not undergo AF ablation for rhythm control.[10]

The study by Kalman and colleagues has limitations: first, there were <100 randomized patients. As a consequence, the baseline characteristics in the randomized groups were not entirely balanced, as illustrated by numerically higher CHA2DS2VASc score (see above) and more patients with paroxysmal AF in the delayed ablation (63%) as compared with the early ablation arm (46%). These imbalances may have favoured delayed AF ablation. Second, the relatively small number of patients reduced the power of the study to detect a small difference in recurrent AF. The limited power is partially mitigated by multiple ways to compare recurrent AF that all demonstrate retained effectiveness of delayed AF ablation. In addition, the difference in observed recurrences is quasi identical, rendering clinically relevant differences less likely. Third, the study was executed in highly experienced centres with high ablation quality. Whether AF ablation retains its effectiveness when delivered by less experienced teams is not known. Fourth, follow-up times differed between randomized groups by design (1 and 2 years follow-up after randomization). However, this difference is well addressed in the presentation of the results. Fifth, the study enrolled a relatively young and otherwise healthy population of AF patients. It remains unclear whether similar results will be found in patients with a high comorbidity burden.

The 3-year outcome data of EARLY-AF show that AF burden is almost undetectable 3 years after AF ablation (0.0%), but also very low in patients receiving antiarrhythmic drug therapy (0.24%).[11] AF ablation slows progression of paroxysmal AF to chronic forms,[12] but progression occurs in only 2–5% patients per year, and some patients do not progress for decades. Taken together with the findings from the present study, these data suggest that antiarrhythmic drug therapy is a reasonable initial rhythm control treatment option. This may apply to patients without severe symptoms and to those who dislike interventions. There will be other patients who need quick access to AF ablation, e.g. those with severe symptoms, patients with arrhythmia-induced cardiomyopathy, or patients who demand the most effective treatment as early as possible. These and other considerations will guide the timing of AF ablation in individual patients (Graphical Abstract).

A few years ago, only every eighth to every fourth patient with AF (12–25%) was treated with rhythm control therapy. Two-thirds of all patients with newly diagnosed AF qualify for rhythm control for outcome reduction based on the EAST-AFNET 4 enrolment criteria.[6] This rise in patients needing rhythm control therapy already creates practical and organizational pressures, especially in countries where AF ablation services need to grow to meet demand. These pressures will intensify as early rhythm control is implemented into care pathways. Furthermore, not all healthcare systems can afford to provide immediate AF ablation for all patients. The demonstration that delayed AF ablation retains its effectiveness is therefore a relief for all who are involved in the organization of AF care and need to meet the increasing demand for rhythm control therapy and AF ablation.

Conceptually, safely delivered AF ablation could be the therapy of choice for delivering early rhythm control to reduce outcomes. This concept is supported by the effect of AF ablation on rhythm outcomes and by the predominant mediation of sinus rhythm at 12 months for future outcome reduction in EAST-AFNET 4.[13] These considerations call for outcome trials comparing AF ablation with medical therapy for the prevention of cardiovascular outcomes. Such trials need to integrate the progress made, and the lessons learned from analysing EAST-AFNET 4[3] and CABANA.[14] Based on the present study, such trials can accept a slight delay in patients randomized to AF ablation.

In summary, AF ablation retains its effectiveness in preventing AF after a year of waiting on antiarrhythmic drug therapy. This finding will be a relief to patients and care teams faced with waiting times. Conceptually the findings also underscore that rhythm control therapy, including early rhythm control, is a long-term treatment strategy that requires balanced choices between antiarrhythmic drugs, AF ablation, and other interventions protecting and restoring the integrity of the atria.

Eur Heart J. 2023;44(27):2455-2457. © 2023 Oxford University Press

Copyright 2007 European Society of Cardiology. Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.