This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Robert A. Harrington, MD: Hi. This is Bob Harrington from Stanford University, here on Medscape Cardiology and theheart.org. Today, we're going to extend a conversation that we've had several times over the past few years in talking about the cardiovascular complications of COVID-19.

At the very beginning of the pandemic, we, on this show, talked about some of the acute cardiovascular issues surrounding the infection, talked about how people with cardiovascular disease might be at increased risk for infection, talked about some of the cardiovascular complications, began to explore topics like endothelial dysfunction and thrombosis, and really, I think, set the stage for the next few years of thinking about and watching research take place that dealt with some of those acute manifestations.

As the pandemic progressed, we also became interested in talking about what was being observed in long COVID-19. In particular, this past year, we had a conversation with an investigator who had really looked carefully at the US VA database to begin to understand what might some of the epidemiologic observations be around an increased incidence of cardiovascular disease among a group of patients who had suffered acute COVID-19 infection and now looking out 6 months, 1 year, or more than 1 year later.

Today, I want to revisit the long COVID-19 story with a guest from the United Kingdom who is contributing an enormous amount of work in a short period of time, dealing with the pathophysiologic manifestations of what I'll call long COVID-19 or post-acute COVID-19 syndrome, to really begin to tease out what might some of the biology be, how might that give us insights into potential treatment, and to begin to understand where we may go in not only understanding what's going on with this group of patients but also offering potential treatments, including in clinical trials.

I'm really pleased and feel honored to have as our guest today, Dr Betty Raman. Dr Raman is an associate professor of cardiovascular medicine in the Radcliffe Department of Medicine. She's also a member of the Oxford Biomedical Research Center at the University of Oxford in the UK.

Betty, thank you so much for joining us here on theheart.org and Medscape Cardiology.

Betty B. Raman, MBBS, DPhil: Thank you, Bob. It's a real pleasure to be here.

Multiorgan Systems Effected

Harrington: I've been reading through your work over the past few days, and it's been an enormously productive period for you. I'm curious, as a cardiovascular medicine specialist, what grabbed your attention during the course of the pandemic and really started this research interest over the past few years?

Raman: Yes, Bob. That's really interesting. I have been, obviously, much like everyone else, intrigued by coronavirus and the devastation it's caused across the world, both from a health perspective and indirectly from an economic perspective.

My background is that I studied internal medicine before cardiology, so I have a general understanding of systemic diseases, including infectious diseases, and I then went on to specialize in cardiology. I've always been interested in internal medicine. When the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded, I was particularly interested in its effects on the heart and other organs.

Harrington: As a chair of a Department of Medicine, I'm really happy to see that subspecialists remain interested in general internal medicine because I do think that one of the things that sets medical subspecialists apart is this foundation of internal medicine. Good for you that you built upon that.

You published a paper very early, I think it was around January 2021, so less than 1 year into the pandemic, where you looked at what you called, if I remember right, the medium-term effects on vital organs. You started getting into this notion that there was multiple organ system involvement that translated into multiple types of symptoms. That paper strikes me as having laid the groundwork for many of the next things that you began to do. Do you want to comment on that? Maybe tell us how that paper came to be and how that ignited your interests?

Raman: Absolutely. In the early days of the pandemic, there were reports from postmortem studies and biopsy studies shedding light on the prevalence of organ injury or the potential mechanism by which COVID-19 could be affecting other organs. Obviously, these investigations came about when there were reports of death and people being critically unwell, requiring intensive care and multi-organ support. At this point, it was clear that coronavirus infections were not only a threat to the lungs and the respiratory system but also to other organs. In particular, there were some early studies demonstrating a high prevalence of myocardial damage in people who were previously hospitalized.

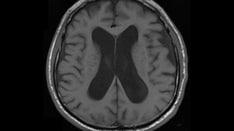

With all these studies emerging, I became interested in ways by which we could assess this damage noninvasively. One of the things that I have developed expertise in while I've been here in Oxford, having done a PhD in this field, is evaluating the role of MRI in assessing cardiovascular diseases. I applied some of that knowledge and expertise to better understand and to get further insights into the effects of coronavirus infection on the heart and multiple other organs.

I also integrated some of my internal medicine knowledge, so I looked at other ways of measuring the effects of coronavirus infections on holistic aspects of health, including exercise tolerance using cardiopulmonary exercise test. I was interested in how coronavirus infection could affect the whole person rather than a single organ because it was clear from early reports that the infection had a devastating impact on the whole body.

Harrington: It's interesting. There was a paper that came out this week that you may have seen from a Scottish group looking at 30,000-plus individuals who had been infected and then a control group who hadn't. What struck me was two things, one of which is that with regular follow-up with surveys that 6% of people in that survey said that they were not better, that they had not improved from their initial infection. These were asymptomatic infections.

The second thing they reported was that 42% of people reported a partial recovery, so almost 50% of people are not back to normal. That surprised me — that 42%. Does that surprise you as somebody who's been in the field or is that in keeping with what you've been seeing?

Raman: I'd say that those figures make sense in the pre-vaccine era, so before the vaccine was out, before Omicron, and before the variants had evolved. I think we need to reassess those figures in the current era of vaccines and emerging variants. I do think that the population are developing and building immunity that is protecting us not only from severe disease but also long COVID-19. I'm quite confident that those figures are probably correct if we were to look at people before the vaccines.

Top Hypotheses for Long COVID

Harrington: It's interesting. Within that paper, they did mention something that you're touching upon, which is that the degree of improvement was definitely associated with the initial severity of infection. If one accepts that one of the main things, as you've said the vaccine does, is diminish the severity of infection, it would make sense then that over time, we may see fewer symptoms. Your point is well taken.

What do you think some of the underlying biology of the long-term effects is? Is it this endothelial dysfunction people have talked about? The one was talked about it as an endotheliopathy. Is it microthrombosis in multiple organ system? Is it just ongoing inflammation? What are you finding and what are your hypotheses around this?

Raman: This is an evolving field as well, as we continue to do experiments and study large number of people. There are multiple mechanisms that are put forward by experts in the field, and I don't think any single mechanism explains this multisystem syndrome that people are experiencing.

I think the dominant hypotheses are, one, of inflammation, either due to persistent viral reservoirs or due to an autoimmune process, although the evidence for the latter is diminishing over time, which is autoimmunity.

The second hypothesis is one of vascular inflammation. In the early days, there were studies showing isolation of viral particles in the endothelial cells. Then there were more studies looking at viral particles in pericytes, and pericytes are the supporting cells in the vasculature that may be infected and may be talking to the endothelial cells and surrounding tissue to promote inflammation.

Then there's also been evidence to suggest that the fat around the blood vessels may potentially be signaling or sending out signals that might contribute to vascular inflammation. That's another hypothesis that people are currently evaluating and testing to see as to whether that might explain the symptoms.

Another mechanism is the possibility of other viruses being reactivated in the context of coronavirus infections. This occurs because of something called immune exhaustion. Essentially, it's the consumption of white cells and lymphocytes, and as a result, the body's immune system is weak. In that context, other viruses might be reactivated like Epstein-Barr virus or other viruses that are known to also present with persistent, multisystem manifestations.

A fourth hypothesis that's gaining popularity is mitochondrial dysfunction. The evidence for this comes from cardiopulmonary exercise tests of individuals who clearly have no lung or any cardiac involvement on advanced tests, but they have signs of lactic acid buildup in their muscles quite early on in the exercise regime to suggest that aerobic metabolism might be affected. We've been doing some studies involving studying skeletal muscle metabolism in patients with fatigue-dominant long COVID-19 and we're seeing signs of abnormal metabolism in the muscle.

Some other mechanisms being considered are microbiota being disturbed or dysbiosis in the gut, which interacts with the immune system and essentially disrupts the homeostasis within the body, contributing to persistent expression of certain cytokines. Cytokines are in the blood. They circulate around to various organs, and that might explain the multiorgan manifestation symptoms that people experience.

Therapies and the Virus/Vaccine Myocarditis Question

Harrington: That is one of the best set of explanations for the various pathophysiologic mechanisms underpinning the diseases that I've heard. Thank you for walking us through that.

The mitochondrial one really interested me because I hadn't thought much about it and hadn't heard much about it until I began to read your papers. As I understand it, you're also engaged in some clinical studies that are beginning to examine how we might address that as a target in an intervention. Would you talk a little bit about that?

Raman: Sure. We've just completed a phase 2a clinical trial of an endogenous metabolic modulator in patients who have fatigue-dominant long COVID-19 and in whom there is no other evidence of organ injury. Essentially, they've had extensive cardiac scans, lung scans, and all these tests are normal. We do a scan of skeletal muscle, aerobic metabolism using a technique called 31-phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy. We've demonstrated that these patients have abnormal metabolism.

In a blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial, we evaluated the efficacy of a therapy called AXA1125. Essentially, it is a combination of five amino acids on a branch-chain amino acid, which was shown in this trial to significantly improve symptoms in comparison with placebo. Bear in mind, all the patients and doctors were blinded. It did have some promising results and we're planning to now undertake a phase 3 trial of this therapy in patients.

Harrington: Fantastic. In our own environment here at Stanford, we have a very, very busy long-COVID-19 clinic and having the option of down the road and have both people participate in clinical trials but then also, ultimately, having therapies that might benefit them is obviously critically important.

I want to get to the last topic, if you're willing to indulge me, and that is the balance between the risks associated with the mRNA vaccines. In particular, people have talked about, in young men, specifically, the risk for myocarditis as a consequence of the vaccine vs the risk of remaining unvaccinated and potentially elevating your risk for a severe infection, which might translate into an elevated risk for a long–COVID-19 sequelae.

Can you walk us through that and help our listeners understand what the evidence is supporting right now?

Raman: There are a number of investigations and studies that have shown that there does appear to be a slightly increased risk for myocarditis following administration of mRNA vaccines, in particular, Moderna and Pfizer. The key message is that this risk is really low. It is somewhere between six and 10 per million cases. Let's stick to myocarditis after coronavirus infection, which is 40 per roughly 40 per million, this risk for myocarditis following an RNA vaccine is really negligible.

There have been studies which have evaluated the pattern of cardiac injury following mRNA vaccine in a number of really reputed journals, Radiology, and some of the imaging journals, including Circulation Cardiovascular Imaging, where they show that actually the extent of scar damage caused by myocarditis in the context of mRNA vaccine is actually very small.

In terms of risk, even though someone has myocarditis, that risk is far lower than the risk associated with a severe infection, myocardial injury linked to that infection, or myocarditis. We're not just talking about myocarditis from COVID-19, but everything else that comes with it if you consider someone with severe infection.

Harrington: That's an important message that I wanted to make sure our listeners heard and something that we need to just keep reiterating from the medical professional side of things.

Betty, this has been an absolutely terrific review of some really important work that you've got going on understanding the sequelae of COVID-19 infection. I want to thank you for sharing your knowledge here with us on Medscape Cardiology and theheart.org. I think our listeners will appreciate hearing from not only an expert but also someone who has ongoing active investigation in this area over the past few years. Congratulations on what you produced thus far, and we look forward to seeing your clinical trial results in the months and years ahead. Again, thank you.

For our audience, thank you for tuning in. Our guest today has been Dr Betty Raman, an associate professor of cardiovascular medicine in the Radcliffe Department of Medicine at the University of Oxford, United Kingdom. Thanks, Dr Raman, for joining us here.

Raman: It's a pleasure. Thank you, Bob.

Robert A. Harrington, MD, is chair of medicine at Stanford University and former president of the American Heart Association. (The opinions expressed here are his and not those of the American Heart Association.) He cares deeply about the generation of evidence to guide clinical practice. He's also an over-the-top Boston Red Sox fan.

Follow Bob Harrington on Twitter

Follow theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology on Twitter

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube

Credits:

Lead image: Medscape Illustration/Dreamstime/Getty Images

© 2022 WebMD, LLC

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Cite this: Robert A. Harrington, Betty B. Raman. What Do We Know About Long COVID: A Cardiovascular Focus - Medscape - Oct 31, 2022.

Comments