This transcript has been edited for clarity.

John M. Mandrola, MD: Hi, everyone. This is John Mandrola from theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology. I'm here in Barcelona, Spain, at the European Society of Cardiology meeting. I'm really happy to have Professor John Eikelboom from Hamilton and McMasters University. Dr Eikelboom is an expert in anticoagulation, and we're going to talk about this new and exciting thing going on with factor XI inhibition. Welcome.

John W. Eikelboom MBBS, MSc: Thanks very much, Jim.

Mandrola: Tell us what exactly is factor XI and why is it important?

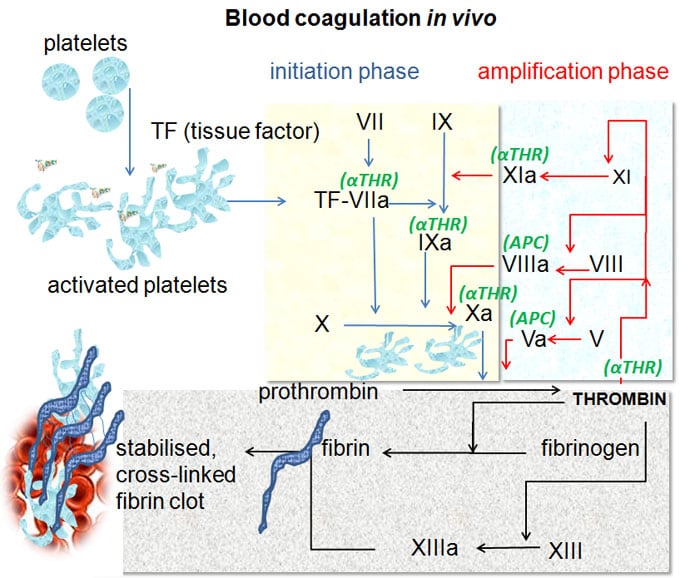

Eikelboom: Well, it's conceptually very simple. Factor XI is a clotting factor. It's high up in the clotting pathway. Some of us remember from medical school two pathways, but we needn't get into the details. We've ignored factor XI for many years, but now there's a new insight that perhaps it's the ideal target for a new anticoagulant.

Mandrola: The problem with anticoagulation is that everything that reduces thrombosis also increases bleeding, but there's something special — at least that's the idea — here.

Eikelboom: Exactly. That's where the two pathways come in. Factor XI sits on this contact pathway and it doesn't have much to do with controlling bleeding. Factor XI is not important to hemostasis, but it is critically important for thrombus formation.

We can leverage this dissociation. If we target factor XI, we can stop a pathologic clot from forming but still allow normal clot formation.

Mandrola: This sounds like the Goldilocks type of anticoagulant.

Eikelboom: Indeed. We've heard it before in the development of antithrombotics. We love to hear about molecules that are going to do the right thing and have no side effects. It remains to be demonstrated that targeting factor XI will achieve this holy grail of antithrombotic therapy. We need the trials for that.

Mandrola: Wait a second. Are you telling me something that makes sense may not work clinically?

Eikelboom: Indeed. Many things make sense, so we deliver a hypothesis. That's why we do the science. The world loves new hypotheses. We, as clinicians, love these new concepts. But, unless we do the proper randomized trials, we don't know the answer or the truth. Many of our hypotheses are ultimately proven to be wrong.

Mandrola: Tell us more about how something can stop clot formation or block thrombin formation, so-called amplification, but yet not effect bleeding. This is strange to me.

Eikelboom: Let me use an example. If I injure myself in a motor vehicle accident and I get a crush injury to tissue, there is a massive amount of thrombin generated. One of those two pathways we talked about, the tissue factor pathway, produces an enormous drive to thrombin generation and we form clots.

However, it's a completely different story when we have an acute coronary event because there, we have a plaque embedded in the wall of a vessel that ruptures. We get a small amount of thrombin generation. That thrombin is insufficient by itself to cause an occlusive thrombus. That thrombin needs to be amplified so that we can create or generate enough thrombin to cause a thrombus. That amplification step requires factor XI.

Mandrola: How did one figure this out? I was reading that it was almost a fortuitous discovery.

Eikelboom: Indeed. The best information on factor XI actually comes from hemophilia C, and most of us don't see hemophilia C, but that's the inherited form of factor XI deficiency. People who have factor XI deficiency hardly ever bleed, but there are some exceptions.

We don't fully understand it, but they have a very low risk for bleeding, even if the factor XI level is 1% or 2%, and they're relatively protected against thrombotic events. That really drove the idea that if we could selectively lower this factor XI to very low levels, we'd get our hemostasis. We'd have our cake and eat it.

Mandrola: There are many ways to go about this, aren't there? There are different drugs and different mechanisms. Give us an overview of what we're talking about.

Eikelboom: There are three common approaches. One is with an antibody. The antibody basically binds to factor XI and gets rid of it, so we lower factor XI levels. The second is this exciting technology of an antisense oligonucleotide, a piece of genetic material, that stops the cell from producing factor XI. Like the antibody, you lower the levels down. Both of these are parenteral agents; they're given by injection.

The third, and perhaps the most exciting, are the small molecules that are taken orally. There are several companies that make these. They target not factor XI, but XIa. It's a bit of a nuance, but they target the activation product of factor XI when it gets fired up.

Mandrola: I remember from the American College [of Cardiology] meeting this spring, there was a study in atrial fibrillation that showed some potential positive signals in terms of lower bleeding, but not enough thrombotic events. Give us a view of what's going on in the trial world now. I think we're in the phase 2 setting, aren't we?

Eikelboom: Well, there's a large number of companies. First, there is a large number of molecules. Even within each of these classes, there are several different molecules. Many of the phase 2 trials are reporting at around this time.

The big picture summary of the phase 2 trials is, yes, we're seeing low rates of bleeding, not always as low as we expected, but generally low rates of bleeding. The trials haven't been powered for clinical events, so we're still not sure how effective these drugs are going to be to prevent stroke, myocardial infarction, and cardiovascular death. For that, we need some big phase 3 trials. They're going to happen very soon.

Mandrola: Do you think that the phase 2 trials that we are seeing now are enough to warrant any optimism about the phase 3 trials? The reason why I ask is because the direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are pretty good.

Eikelboom: That's the big question. As usual, you ask the right questions. I think that's what everybody is asking. Will the newer agents produce a sufficient reduction in bleeding, and of course, will it be effective to warrant them replacing these wonderful drugs we have, such as dabigatran, rivaroxaban, edoxaban, and apixaban? We have an astonishing array of effective anticoagulants.

I just want to say one thing about this. If we look at the big atrial fibrillation trials of DOACs vs warfarin, we forget that 1 in 10 people each year, in all of those trials, whether on warfarin or a DOAC, have bleeding — 1 in 10. Major bleeding is much less common.

Bleeding is still a big issue. Where bleeding is most important is in the patients who we currently don't treat because of bleeding concerns.

It's not all about head-to-head comparisons. With the emergence of DOACs, we expanded the market. We still have one quarter of our patients with atrial fibrillation who don't get anticoagulation, mostly for bleeding concerns.

Mandrola: Even if this factor XI strategy is equally good thrombotically, if there was less bleeding, that would be a clinical advantage?

Eikelboom: That would be a clinical advantage, but there's definitely going to be a price tag, so we need to see a big reduction in bleeding. That's where the big question is.

Will we see less bleeding? I suspect we will based on what we know so far from the early studies. Will we see efficacy? We need the phase 3 trials to demonstrate that? Will the advantages be big enough that the extra cost of these new drugs will displace the other ones?

Mandrola: Excellent. This was extremely helpful in helping me understand this, and I'm really grateful that you came on. Thank you very much.

Eikelboom: My pleasure. Thank you.

Follow theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology on Twitter

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube

Credits:

Images: Wikimedia Commons

© 2022 WebMD, LLC

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Cite this: Will Factor XI Be the Goldilocks Anticoagulant Target? - Medscape - Sep 26, 2022.

Comments