It's a Small World columnist Jessica Sparks Lilley, MD, interviews Priyanka Bakhtiani, MD, director of the new Children's Hospital Los Angeles clinic for survivors of childhood cancer with endocrine issues. Dr Bakhtiani is also secretary for the Pediatric Endocrine Society's Tumor Related Endocrine and Neuroendocrine Disorders special interest group.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Jessica Sparks Lilley, MD: I'm so excited to highlight your work. I have a strong interest in late effects, as it was one of my first exposures to pediatric endocrinology. I have a cousin who we call my twin brother as he is only 3 weeks younger than me. He's doing great now that we're almost 40. But in the 1980s, he had leukemia and was treated with intracranial radiation when we were 3.

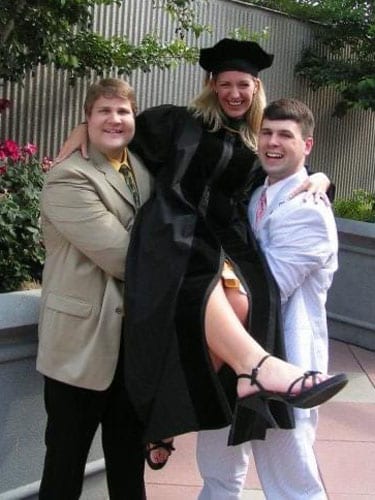

Jessica Sparks Lilley with her cousin, Jordan (left), a childhood cancer survivor, and her husband, Smith (right), at her 2007 medical school graduation.

He ended up having growth failure when we were 10. I remember talking about the suspected cancer risk of growth hormone treatment at family gatherings. All those decision points. His family chose to pursue treatment with growth hormone, and it did everything it was supposed to do.

Can you tell me a little bit about what drew you over to late effects?

Priyanka Bakhtiani, MD: When I was a resident, I rotated through Memorial Sloan Kettering, where I became interested in oncology and transplantation. I had a patient pass away when I was on call, and I knew I couldn't do it as a career.

Then I fell in love with endocrinology. In my endocrinology fellowship, my clinical mentor ran the endocrinology late effects clinic. My research mentor was actually an oncologist who worked with immunotherapy, so that's what my research was.

My husband is a pediatric oncologist, so I have him on speed dial and can ask, "Hey, what does this chemotherapy agent mean, and what kind of category does that fall in?"

I feel a lot of personal connections. By preemptively screening and providing multidisciplinary care, we're able to help these patients live a relatively, if not a completely, normal life. After what they've gone through, we do what we can to make a difference. It's pretty awesome.

Lilley: How early in the process are you getting involved? When do you think is a good time for the endocrinologist to be added to the care team?

Bakhtiani: That's a question for the ages, right? Currently, the guidelines recommend you should start screening at that 1-year mark, and that's when patients get referred to survivorship clinics. I think the advantage of having a dedicated clinic and being that point person is that I can screen them even as these kids get diagnosed. We're establishing that continuity before they get to that survivorship stage.

If they have a relapse a year later, I had that year. We communicate regularly with our oncology team. It makes a difference to have that collaborative care and have those communication channels open. They don't have to be a year after being in remission. We can start testing and identifying these things sooner as well. It definitely has been very insightful.

Lilley: Where are our biggest opportunities as pediatric endocrinologists to improve our care for these patients? What do you see as our biggest frontier, the next big thing we need to consider?

Bakhtiani: This field is changing as we speak. Our excellent oncology colleagues are working on more focused treatments and prevention issues. We're also seeing some novel therapies with newer endocrine side effects.

The biggest things we can do as endocrinologists are stay on top of it, be involved, and try to identify these trends sooner than later.

It comes to a team effort with oncology because a lot of times, these diagnoses will get missed, because the oncologists are screening and they might not be familiar with all the nuances of endocrinology. We can screen these kids appropriately and manage and prevent any clinical effects from endocrine issues. It makes such a big difference in these patients' lives. Having that teamwork allows us to look at the patient from all sides and make sure that these things do get identified.

Lilley: We have to have a seat at the table. It's important to be in the room where these guidelines are being written, making sure that our trainees are exposed. We need to claim our space and say, "Yes, you [as oncologists] are going to help them survive their illness, and we're going to help them for the rest of their lives, to make sure we're optimizing everything in their health, so they can have their best quality of life and that's everybody's shared goal."

What are the most common complications that you see as an endocrinologist?

Bakhtiani: We see many of the same complications that are consistent with the available data. We see pituitary growth failure, as you mentioned. As you know, most kids who undergo cancer treatment will get alkylating agents [and thus we have fertility concerns]. Short stature is very common. We are seeing more metabolic effects — maybe COVID-19 has something to do with it? We're seeing low bone mineral density, a topic that endocrinologists love to talk about.

Lilley: Let's talk about the impact on quality of life and making sure that those concerns are addressed. Tell me a little about fertility and alkylating agents. What do we have to offer a boy who comes in who has had exposure to alkylating agents? Is that a conversation you want to have before therapy starts? That's a very open-ended question, and the answer is way different for boys and for girls. But we need to make sure we think about 15-20 years down the road, when they begin sexual development that will lead to them being parents (if they want to).

What are the options available to them, and how have these changed over recent years?

Bakhtiani: All patients are counseled about fertility preservation and diagnosis. But it's not really the time when people are thinking about fertility. They're not thinking about 30 years down the line, "Do I want to have kids or not?" They're thinking, "I want to live for the next year." There's a lot of information being offered to them.

Gamete preservation is an option for teenagers who are postpubertal. I don't think the rates of people taking up those options are really high in our institution. When these kids are in remission and I do see them in that survivorship clinic, we're focusing on thriving not just surviving, and that's when these things come up.

If I ask a teenage boy, "Do you want to have kids when you grow up?" and the answer is "No, I don't want to talk about it," I try to have an open communication with them and let them know it's okay to think about this at this age. Ask them open-ended questions identifying their known priorities in life and then guide them accordingly.

I think we could do a lot better than we're doing right now with fertility preservation.

Lilley: There's a lot of fires at once, as we see with anybody with a life-changing diagnosis. They remember so little from the initial meeting. They're in shock. I'll have people say, "You never told me," even though we talked about it. Even though we think we do a good job with this, we have to keep in mind that we're meeting people on the worst day of their lives, when they're having this traumatic diagnosis for their child.

We talked about boys. What are the options for girls? Are they getting better? When I was in training and thinking about these questions, there wasn't a lot on the table for girls. People say, "Freeze her ovaries. We'll freeze her eggs." But the technology is not as great as people think it is.

Has this gotten better? What is there available to young women who are coming to your clinic?

Bakhtiani: I definitely think oocyte preservation is an option. The rates of girls asking for it, or families — especially if it's a teenage girl — is a little higher than what we see in males. But then there's the pressure of, are you going to wait for the next 4-6 weeks and do this vs are you going to start your chemotherapy sooner?

The other barrier is insurance. Insurance does not cover fertility preservation, so it has to be paid out of pocket, limiting it to a certain percentage of our patients. We're in Los Angeles, and more than 75% of our patients are publicly insured. A huge proportion of our patients are Hispanic and often don't speak the same language, so in terms of providing resources to our patients and communication, that is a priority at diagnosis.

We have patients whom, in collaboration with reproductive endocrinology at the University of Southern California, we would put on puberty suppressors as they start chemotherapy. This is debatable, as there's mixed evidence, so we would have that conversation with patients. There is the thought that suppressors temporarily put your ovaries on pause, and this maybe prevents some oocyte destruction, giving us a higher chance of being able to proceed with oocyte preservation.

Many of my patients will go to the endocrinologist 6 months after chemotherapy and still have options available to them. I think from a purely early hormone screening standpoint, we do check anti-müllerian (AMH) levels annually on our female patients who did undergo either alkylating agents or radiation to the abdomen/pelvis. Based on that, we would direct our counseling.

Lilley: You also have to have conversations about contraception, as many have variable fertility. I've seen kids who were told they would have trouble having children, and they have no trouble and they have surprises. Is that part of your conversation? It's interesting to have to have a conversation out of both sides of your mouth, but is that something you talk about in your clinic?

Bakhtiani: I definitely try. We have a large amount of information to cover in clinic, so I think we could probably do a little bit better on that front, but we definitely discuss it when we're having that conversation about fertility. We make it a point to mention that, yes, there is a real big chance of issues with fertility, but that doesn't mean [it will definitely or necessarily be a problem]. I think we need to be talking about contraception at more appointments.

Lilley: We need to do that in all areas of endocrinology. We need to do it at every opportunity that we get. Kids with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) are told they'll have fertility difficulty. We don't always do the best job of making sure that they are having planned pregnancies and are becoming parents when they are ready.

I'm very curious about some of the new immunotherapies and checkpoint inhibitors we're seeing, especially from our adult oncology colleagues.

What are you noticing with that novel therapy in kids? Which ones are being used frequently, and what are the downstream effects we need to be aware of as endocrinologists?

Bakhtiani: We're starting to see immunotherapy now, and my prediction is that 5 years down the line, that's basically [where the main conversation on late effects will be]. We're talking about it a lot in the survivorship world.

We're trying to identify those risk factors as we go, but the one thing we know is that normally our body uses those immune checkpoint inhibitors to prevent an immune reaction against our own body. Those inhibitors actually allow those cells to say, "Hey T cells, you can now go kill that cancer cell because it's not something that's our own." When we do that, we open the tap for all the other cells in our body, which is why we see that higher risk for autoimmunity.

I know we do see a higher risk for hypophysitis or autoimmune diseases, which is unique, because we see a higher prevalence of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) deficiency. There are reported cases of Addison disease.

What I'm seeing more of right now in the literature, and in at least one patient in our institution, is that patients will get PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitors and then present with new-onset autoimmune diabetes. That should be on our radar as we start to use these agents more.

Lilley: You've been in practice for a while, like myself. Many of these treatments didn't exist when I was in training. There's so much to stay abreast of! I'm very grateful that we'll get this out into the world so everybody can know.

What are some of the unique challenges that you face working with this population? One thing I think people forget is that when a child has cancer, everything stops for the family and they have a big financial stress. Even if the medical care is covered, the parents aren't working as much, and so their savings can be obliterated. I've seen that even with patients of mine who've been treated at St Jude, where everything is free. We need to talk about the financial implications, but what other things are you seeing in taking care of these children?

Bakhtiani: The biggest barrier in my mind is this is not the only thing they have, right? A child who got alkylating agents and total body radiation now has a normal growth velocity. You examine them in clinic and you're like, this kid's fine, but then what's going on is that the testicles are prepubertal because they're actually in early puberty and making a whole bunch of testosterone that's causing their growth velocity to be high. But they also have growth hormone deficiency, and it looks like their growth velocity is normal.

From a science perspective, the big barrier is that it's easy to miss things. You have to have an endocrinologist who is familiar with and looking out for these things.

Another big thing is the fact that they had cancer, they went through the toughest time ever in their life, and now they're done with it. Everyone tells them, "Okay, you're cancer-free, you're a survivor, you're done," and then we turn around and say, "Just kidding; you have to still miss 5 days of school per year because you have to see these five doctors every year." Parents still have to allocate not just transportation and financial resources, but also 5 days a year when they're missing work.

We try to schedule multiple provider appointments for the same day. We're very flexible with converting appointments to telehealth, for patients who are not able to come in. Collaborating with the oncology team means that I know I will see this patient in clinic.

I'll start screening — whatever screening I would recommend — or even [begin] management and collaboration with oncology even before the patient sets foot in the endocrine clinic. This minimizes the number of actual visits they need to make to the clinic. Also, having a social worker in clinic is helpful because they can address the factors that I can't address.

Another barrier is going back to the science, as we talk about the fact that things are changing so fast that even if I memorize all the Children's Oncology Group (COG) guidelines right now, there is going to be a new therapeutic; there are going to be changes in the way we think about things.

For example, methotrexate is associated with low bone mineral density. The guidelines are now going to change, and we know that's not such a high risk when you compare it with radiation or high-dose steroids. So you need to be on your toes and you need to be aware of the standards of care, so that you can provide them.

The other thing I think about from a clinical standpoint: You get 30 minutes to see a new patient, but they come to you with years of history you need to be familiar with, including the type of therapeutics they got and what complications they've had since then.

It does fall on the provider to spend time reviewing that chart in advance, so we can guide and help our patients navigate.

I was thinking about no-show rates, because that's a huge, huge thing anytime we have meetings in the survivorship world. Patients are done with cancer, and now you tell them, "You could develop a thyroid issue that we're going to test you for, but it could be a year from now or 30 years from now." It doesn't feel as important to them. To the credit of our oncology team educating them and to our team's efforts and collaboration since we opened the late effects clinic in October 2021, our attendance rates have been 81%. If we can go a little out of our way to help support our patients and educate them, that does help address these barriers.

Lilley: Do you share clinic space with your oncology colleagues, or in what setting are you seeing these patients?

Bakhtiani: I see them in the endocrinology clinic, but in collaboration as we talk and communicate with the oncology team. There's always that open line of communication. The goal is to have a multidisciplinary clinic where patients come in and see all the providers they need to see at one time.

Lilley: How would you advise an endocrinologist like me who's in the community and maybe a little bit past training, and we have a patient show up in our clinic who is asking questions? I'm on an Air Force base, so I'll get people who have moved in from all over the country, sometimes with records, sometimes not. They show up and say, "Hey, I had a polycystic astrocytoma, and I was treated when I was 4. They said I needed to see an endocrinologist."

Where would somebody like me turn? Of course, I've got friends that I call, but let's pretend I don't. If I don't have your email address, where do I go to find guidance to help patients like this?

Bakhtiani: I would say the COG guidelines are the place to start. I will shamelessly plug the Pediatric Endocrine Society and the Tumor Related Endocrine and Neuroendocrine Disorders Special Interest Group, where we're working on developing more and more educational modules and handouts for our patients. We have a special interest group that meets every few months, and we talk about these issues and developing collaborations and stuff, so if you're really interested, that would be a really great place [for information]. But the Pediatric Endocrine Society would be a good place if you just want handouts.

Lilley: What is your current area of research?

Bakhtiani: We're starting to make a registry for our patients — a list of our patients with their diagnoses and cancer treatments. That way, it becomes easy for us to identify trends, but even in the future if something is identified, it's easy for us to look back and go back to the patients that would be at risk.

I'm also working on identifying whether obesity is something that is really, really prevalent in the patient population that we see. They're already at high risk for cardiovascular morbidity, but then you add obesity plus potential hormone issues, so their risk is really high. Obesity is an epidemic; everyone wants to do things about it; and in general, people are using weight management medications more. But there's almost a resistance to or fear of using these medicines in cancer survivors, because these patients are not like all our other patients, as they've gone through a lot.

Is it safe? Is it effective to put them on weight management pharmaceuticals? That's something that we're studying, and we're also assessing provider comfort.

Lilley: I'm so thankful. Anything else? You have an open microphone to anybody who wants to read the column. What kinds of things do you wish that everybody working in the pediatric space knew?

Bakhtiani: About half of the patients that recover from cancer will end up having an endocrine issue, and a lot of patients have childhood cancer; the incidence is increasing over time. If you're between 1 and 20 years of age, you have a 1 in 282 risk of developing childhood cancer, and 1 in every 500 adults is a childhood cancer survivor. My take-home point would be to let everyone know that there are resources that you can look at.

Hormone Research published a special edition, which featured mini-reviews all about childhood cancer survivors. That would be a really good resource as well.

The first survivorship patient I saw was a patient referred to us by a general pediatrician for weight gain. The family had been telling this patient you're lazy, you don't do what you're supposed to. We reviewed the patient's history and found they had brain cancer 7 years ago, and we found out that this kid had hypothyroidism, testosterone deficiency, and growth hormone deficiency — all of which are fixable.

But by the time we saw this child, as a teenager, they'd already had their growth plates fused, so there was not much that we could do. I think you're absolutely right that pediatricians need to know about this.

Lilley: One of the things that I think we can do as endocrinologists is to continue to champion these patients and keep that same kind of energy of support. Thank you so much for your time.

Jessica Sparks Lilley, MD, is the division chief of pediatric endocrinology at the Mississippi Center for Advanced Medicine in Madison, Mississippi. She became interested in pediatric endocrinology at a young age after seeing family members live with various endocrine disorders, including type 1 diabetes, Addison disease, and growth hormone deficiency.

For more diabetes and endocrinology news, follow us on Twitter and Facebook.

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube

Medscape Diabetes © 2022 WebMD, LLC

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Cite this: Beyond Survival: Improving Endocrine Care for Childhood Cancer Survivors - Medscape - Mar 15, 2022.

Comments