Sometimes it's the simplest things that we don't really know. As US medicine became increasingly commercial, the staff that wear more tailored clothing than me sent a monthly report that included how many patients I saw in the office, how many consults I did, and other data items that would go unread had it not been for mandatory monthly meetings with the office manager and quarterly ones with the chief medical officer.

Despite the collected data, nobody in authority thought it important to let me know how effective a doctor I was. How many A1c's or TSH's reached therapeutic levels because of my decisions?

I haven't a clue from my final year of EMR practice or the 40 that preceded it. Did I refer properly? No way of knowing.

In looking at the population that uses our center, how many patients floated around our hospital who might have benefited from latching onto the endocrine section but were never referred?

In the United States, doctors are fully socialized to the fragmented medical maze that we can manage but not remedy. We take pretty decent care of the people at hand but never quite appreciate what whizzes by despite our training, which values conscientiousness and attention to detail. Our processes also have a way of distracting us or incentivizing us to do what is expedient and move on to the next exam room.

But there are places in the world where medicine is more reflective and maybe less random, where we can assess what may not be going as well as we think it is. A study from China, published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, addresses some very basic features of diabetes that doctors encounter in different regions at different seasons among patients with ordinary regional variations in diet. The authors noted trends, as well as a few medical lapses, that could make for improved public policy.

China's health system allows for citizens to attend convenient regional health centers periodically for baseline physical exams. Whether all eligible people avail themselves of the opportunity equitably is uncertain, but very large numbers of people do, resulting in centralized data that can be sorted.

For this analysis, 430 health screening centers in 220 cities distributed across most of the country provided data from about 1.4 million patients for the calendar year 2018. By studying an entire year, the researchers could group patients by season as well as more common categories of age, gender, geography, morphometric findings, and laboratory data. Using widely accepted lab criteria, they could determine which patients had diabetes. Historical data provided information about previous diabetes diagnoses, with lab work normalized on treatment.

The study found the prevalence of diabetes to be about 8.7%, a figure that has been steadily increasing from previous Chinese surveys, consistent with trends elsewhere in the world. The data also showed some of the natural history of weight excess, prediabetes, and the crossover from risk factors to established disease.

Men had higher body mass indexes (BMIs) at younger ages, thus raising their glucose levels earlier in life. Women caught up with obesity and diabetes at about age 60, suggesting that men will have hyperglycemia for a longer segment of their lives, increasing end-organ risks that trend with duration of illness.

In the United States, many of us are familiar with maps showing the distribution of obesity and diabetes by region, state, and county, tracked by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The serial assessments, mapped by color, show the increase in prevalence of both over time, but also changes in the geographic distribution, being most prominent in the Old Confederacy region in 2004 but less obviously regionally dominated in 2017.

The Chinese data, more a snapshot than a serial photo album, also has a regional pattern. The northern provinces seem far more affected by obesity and diabetes than the southern regions. In the United States, industrial-scale food processing and transportation has reduced regional variations in diets. While the food industry is global, making many products available worldwide, in China there remain wheat-dominated regions in the north and rice-based diets in the south.

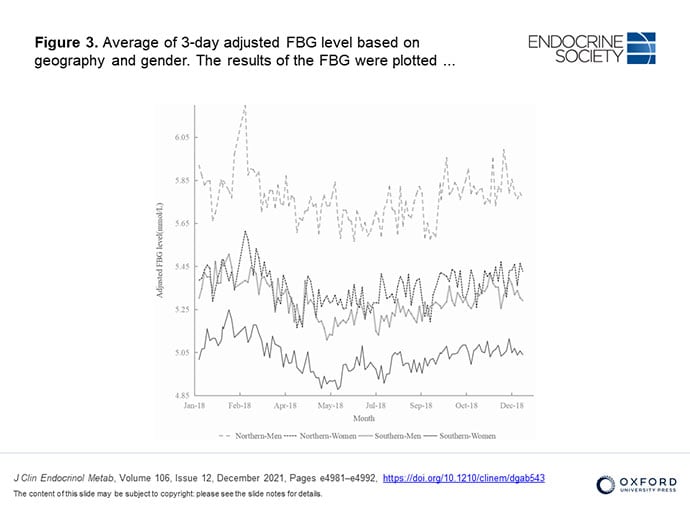

One of the curious findings was the seasonal variation of glucose (Figure). In all regions of China, among all population divisions, average glucose values were lowest in late spring, highest in mid-winter, and rose gradually as the ambient temperatures for each region dropped. For patients with borderline glucose levels, the timing of their preventive exams may affect the ability to detect diabetes and the advice they receive from their physicians.

Figure. Variability of fasting glucose by month in different geographic regions in China.

Some of the more revealing findings involved patient awareness and treatment of diabetes among those found to have it. Only about half of them provided a history of previously established diabetes; the other half was extracted from the lab data. Among those under 40 years of age, only about 20% were aware of their diabetes. Among all those with hyperglycemia, less than 40% had been prescribed medication. This should be familiar to US consultants asked to assess a newly diagnosed diabetic patient, only to read serial lab results on our EMR spreadsheets showing mild to moderate hyperglycemia traceable through the lab records but never conveyed to the patient, and sometimes not to be found in any provider text within the medical record. Attention to minor abnormalities and a heads-up to the patients may fall short of optimal care, despite our advanced, sophisticated data collection.

Among those on treatment, only half had A1c < 7%. And despite universal access to healthcare in China, those from regions of higher prosperity had more favorable data than people attending health centers in less affluent regions.

Hizzoner Edward Koch, the colorful former mayor of New York City, used to ride the subways, introducing himself randomly to passengers, asking them "How am I doing?" Good public policy depends on this. Of note are the many parallels between what happens in an emerging nation with unified healthcare vs our more mosaic-type structure. We miss the results, the subtleties at times, whether borderline testing or what month the evaluation took place. The Chinese citizens came for periodic screening exams, something rarely targeted as priority care in the United States, though we now have Medicare Wellness evaluations for US seniors like me.

While we physicians ordinarily focus on the individual in our exam room right now, aggregate data become the crystal ball to plan for next time. US and Chinese physicians are also highly dependent on policymakers, who turn the findings into clinical expectations to remeasure later, sometimes more successfully than others.

This study makes it apparent that men acquire diabetes sooner than women, will have it longer, need to know about it when it's not obvious, and perhaps need to start monitoring and treating a little sooner. Public policy struggles with global megatrends, seen in the China study as better availability of food and seen in the United States as homogenization of the food supply and availability.

Despite vastly different political systems, one in China where decisions are made with less horse trading and brinkmanship than in the United States, prosperity has a health advantage and easing regional inequities remains a challenge. The study reminds us that the diseases that we see have a universality with global trends but are also particular to their sovereign states. Yet some of what we learn from there can be imported to our patient work here.

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube

Credits:

Lead image: Didesign021/Dreamstime

Image 1: ©Yuanfeng Zhang, et al; 2021. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Endocrine Society.

Medscape Diabetes © 2022 WebMD, LLC

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Cite this: Diabetes Care Challenges Are Similar Around the Globe - Medscape - Feb 15, 2022.

Comments