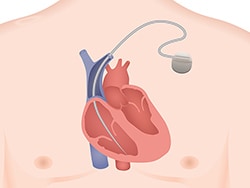

I'd like to share with you a patient presentation that I encountered during an emergency department (ED) shift just yesterday. A 58-year-old man with a history of severe cardiomyopathy, ejection fraction of 15%, and an internal cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) presented to the ED reporting at least five episodes of his ICD firing during the prior few hours. Shortly after his arrival, his ICD fired once again, and the telemetry monitor demonstrated a run of monomorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) leading to the shock. The patient was obviously suffering from the pain as well as the emotional distress of the repeated shocks. He was in the midst of a condition known as the "electrical storm."

Electrical storm (ES) refers to a period of cardiac irritability associated with at least three episodes of VT, ventricular fibrillation (VF), or appropriate ICD shocks within a 24-hour period. My own clinical experience suggests that ES has increased in frequency in recent years, although I am not aware of any studies that have methodically documented the numbers. However, as patients with significant cardiac disease are living longer, it should be no surprise that all of us in the ED are seeing patients presenting with ES more than in the past. This condition has gained greater attention in the emergency cardiology literature as well: Multiple articles on this topic have been published in recent years and they have provided information that is critical knowledge for all emergency care providers. The article by Dyer and colleagues is a particularly excellent review of the topic and worth the time spent reading. I will provide a brief review of the key points.

The vast majority of patients with ES have underlying structural heart disease with histories of cardiomyopathy and a poor ejection fraction. Many of the patients have ICDs. Common precipitants of ES include electrolyte abnormalities, binge drinking, acute infections, cardiac ischemia, acute heart failure, thyrotoxicosis, drug toxicities, and use of antiarrhythmic medications (especially Class IA medications).

Elevated sympathetic tone is a common underlying factor and is usually the result of a vicious cycle of events: Tachycardia (and pain if the patient is receiving ICD shocks) leads to both emotional and physical distress, leading to an increase in catecholamines, further tachycardia, and so on. Consequently, one of the critical elements involved in the treatment of these patients is to break the cycle that leads to an elevated sympathetic tone (described below).

Initial treatment follows the basic principles of advanced cardiac life support. Hemodynamically unstable patients and those with VF should be treated with electricity. If patients have stable VT, however, the type of VT should be analyzed. If the patient has polymorphic VT, that patient is likely to develop hemodynamic instability and require electrical cardioversion.

Following cardioversion, the QTc interval should be evaluated. Polymorphic VT associated with a normal QTc is nearly always caused by acute coronary syndrome, and treatment with antiplatelet medications, anticoagulants, beta-blockers, and cardiac catheterization is indicated. On the other hand, polymorphic VT associated with a prolonged QTc (torsades de pointes) is often the result of electrolyte deficiencies, sodium channel–blocker medications, or a congenital cause. Patients should be treated empirically with a magnesium infusion, and the underlying cause should be aggressively pursued and treated. A more detailed discussion of the treatment of torsades de pointes is beyond the scope of this article but may involve overdrive pacing if cardioversion and magnesium are unsuccessful during initial treatment.

If the patient has stable monomorphic VT, sedation and cardioversion or medications may be used. Although procainamide has gained some support in the treatment of monomorphic VT in recent years, treatment recommendations for ES consistently seem to recommend amiodarone. Amiodarone has intrinsic beta-blocking effects which may be a key reason for its recommendation. Beta-blockers are antiadrenergic and therefore help to break the cycle of elevated sympathetic tone. Additional beta-blockade beyond amiodarone is recommended, although a specific agent and dose are unclear. One study favored the nonspecific beta-blocker propranolol over the beta1-specific blocker metoprolol because of improved lipophilicity, allowing for better central nervous system penetration, but this study is not definitive. Further, central sympatholysis by providing sedation with propofol or benzodiazepines is also recommended.

Electrical storm may also include incessant VF. As noted above, patients with this condition should be treated with standard advanced cardiac life support measures. Recent literature has suggested that double sequential defibrillation (DSD) may be helpful for incessant VF when used early (ie, after an unsuccessful third standard-dose defibrillation), but further studies will be needed before definite recommendations for DSD can be made.

Another study has also suggested that the addition of beta-blockers to the treatment regimen for incessant VF may be helpful. As noted previously, beta-blockade might improve outcomes via sympatholysis, but more data are required to clarify outcome differences. For now, the use of DSD or beta-blockers in patients with incessant VF remains a consideration rather than a recommendation.

The authors also suggest consideration of more invasive options when the above therapies fail, such as stellate ganglion block, placement of an intra-aortic balloon pump with catheter ablation, extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or placement of left ventricular assist devices. These latter therapies are also beyond the scope of this discussion.

Patients with ES who are converted back to sinus rhythm should undergo a thorough workup for the potential underlying cause (eg, electrolyte abnormality, medication effects, cardiac ischemia, etc.) and aggressive treatment once a cause is found.

In Summary

In recent years, there have been significant advances in the care of patients who have underlying cardiac abnormalities, resulting in marked prolongation of these patients' lives. The result is that we are seeing more frequent cases of ES in the ED. These are high-risk presentations with a risk for death 2.4-fold higher than with isolated presentations of VT or VF. The morbidity and mortality associated with these presentations highlight the need for all emergency physicians to be knowledgeable about evaluation and care of patients with ES.

I anticipate that we will continue to see increasing numbers of patients presenting with ES in the coming years. For those emergency clinicians who have not yet encountered these patients, there's no doubt that a storm will be coming your way soon!

Amal Mattu, MD, is a professor, vice chair of education, and co-director of the emergency cardiology fellowship in the Department of Emergency Medicine at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore.

Follow Dr Mattu on Twitter.

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube

Medscape Emergency Medicine © 2021 WebMD, LLC

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Cite this: Amal Mattu. A Cardiac 'Electrical Storm' Is Coming! - Medscape - Jul 26, 2021.

Comments