Pardon the Interruption for Some Math...

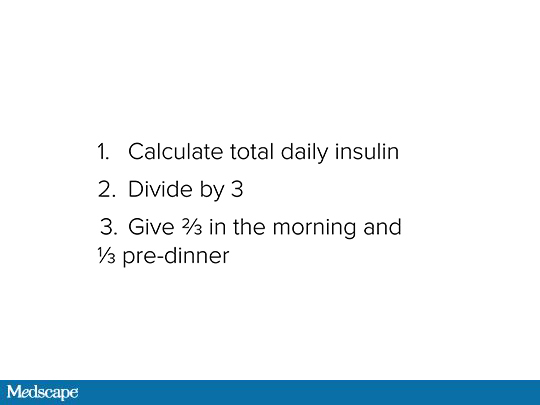

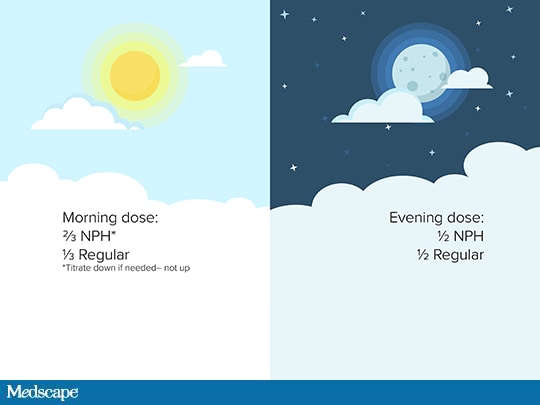

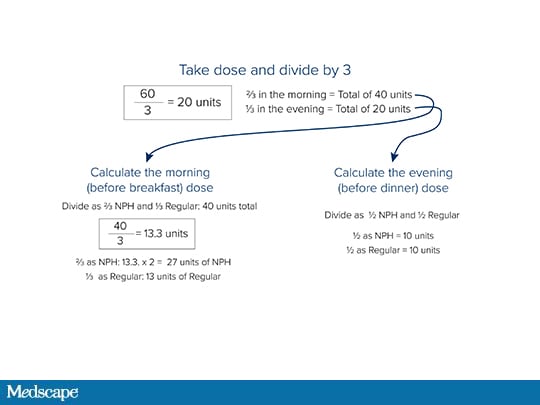

What are the basic steps in switching a patient from an analogue insulin to a split mixed human insulin regimen?

And Now Back to the Discussion

Peters: A few other key points to remember when switching to human insulin:

You must teach patients to draw up and mix insulins from a vial.

Timing is key to avoiding hypoglycemia. NPH peaks approximately 10 hours after a dose, so it means that a patient must eat dinner 10 hours or so after that morning dose. If I'm lucky enough to have a patient who may be able to afford a continuous glucose monitor, then we'll be able to see if the serum glucose levels are going too low, particularly at night.

Regular insulin at mealtime doesn't start to work immediately and should be given at least half an hour before eating. The timing of regular is important. Some patients with type 2 diabetes may eat higher-fat meals and thus need that longer duration of action. It is important that patients actually give their insulin pre-meal and not wait too long. But if they do not give it that far in advance, it's still okay to give it just before eating. If you give regular insulin after eating, the onset of action is delayed and patients might become hypoglycemic because it's not meshing with the timing of the meal. The timing matters.

I want to make sure patients give the insulin and don't go insane about timing. I have seen patients become flummoxed by the timing issue. I want patients to realize that giving regular insulin more in advance is better, but giving it at all is better than not giving it.

People need to also remember the timing for the peak of NPH—which is an intermediate-acting basal insulin that will peak in 4-6 hours and has a duration of about 12 hours. Patients need to carry carbohydrates with them. I always have patients show me in the office that they're carrying carbohydrates on their person. It's not okay if it's somewhere else in the cupboard. It has to be on their person.

Hypoglycemia is a topic that needs to be addressed and readdressed. It should be discussed at every visit with patients who are on insulin, in general, but especially with those on NPH and regular.

Patients you are really worried about, most likely those who are on multiple daily insulin injections, should have glucagon at home. Glucagon is also not cheap. In an ideal world, people who are on insulin would have glucagon so they could be treated if they developed a severe episode of hypoglycemia.

Shubrook: I would also emphasize the importance of teaching patients to use a vial. Particularly if you don't have sample insulin vials in your office, please make sure you get your patients to fill their insulin, bring that vial back to the office, make sure they know how to draw up the insulin correctly, and that they know how to identify good insulin.

A reminder about cloudy insulin versus clear insulin: Regular insulin should be clear but NPH is cloudy.

I have one other question for you. Is there any role for a premixed insulin in this patient?

Peters: The patient you described earlier seems to be doing mixed-dose insulin appropriately, so there may not be a role in this example. I have many patients whose NPH/regular ratio is similar to premixed and they're not correcting high blood sugars with regular. In those cases, it is easier to use premixed than it is to mix it yourself. It really just depends on the patient.

I want to make two other comments. I've had patients who can't draw things up from a vial with a syringe. Perhaps they have poor vision or arthritis that interferes with their ability to do this. In these cases, I have actually drawn up 30 days' worth of syringes in the office. The patients then put that in the refrigerator at home. Then, every day, they take a prefilled syringe for their injection.

I know this isn't the world's most cost-effective, easiest way to spend your patient visit, but if a patient really needs to be on an insulin, can't do it with a vial and syringe, and can't afford a pen, you could draw up insulin in the office or have a family member prepare the syringes.

It gets harder if you're actually adjusting the dose or doing a correction dose, but you can have somebody draw them up in advance for fixed doses. The only important point here is that if someone is giving a different pre-breakfast dose than pre-dinner dose, you have to separate the syringes—sometimes with colored tape.

There are many good ways to help patients with this. Pharmacists can be really helpful. Certified diabetes educators, if you happen to be lucky enough to have one, can be really helpful. As we know, YouTube has a lot of advice—some of it good, some of it not so good.

Ironically, I have found that some of my patients on analogue insulin who are older and now need caregivers actually do better if I have to put them back on regular and NPH. They now have a caregiver who is actually doing it.

The bottom line is that we can help our patients use human insulin in an effective way, as long as we keep ourselves and our patients aware of what is necessary technically, and then adjust and avoid hypoglycemia.

Shubrook: Thank you so much for sharing your expertise and giving us some really practical ways to integrate the use of human insulins into our care of people with type 2 diabetes.

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube

Medscape Family Medicine © 2019 WebMD, LLC

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Cite this: Converting Analogue to Human Insulin: A Step-by-Step Guide - Medscape - May 20, 2019.

Comments